From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about learning vocabulary while learning a second language. For learning vocabulary as a child as part of a first language, see Vocabulary development.

Vocabulary learning is the process acquiring building blocks in second language acquisition Restrepo Ramos (2015). The impact of vocabulary on proficiency in second language performance «has become […] an object of considerable interest among researchers, teachers, and materials developers» (Huckin & Coady, 1999, p. 182). From being a «neglected aspect of language learning» (Meara, 1980, as cited in Xu & Hsu, 2017) vocabulary gained recognition in the literature and reclaimed its position in teaching. Educators shifted their attention from accuracy to fluency by moving from the Grammar translation method to communicative approaches to teaching. As a result, incidental vocabulary teaching and learning became one of the two major types of teaching programs along with the deliberate approach.

Goals of vocabulary learning[edit]

Vocabulary learning goals help in deciding the kind of language to be learnt and taught. Nation (2000) suggests three types of information to keep in mind while deciding on the goals. 1)number of words in the target language. 2) Number of words known by the native speakers. 3) The number of words required to use another language.[1] It is very difficult to know all the words in a language as even native speakers don’t know all the words. There are many specialized vocabularies that only a specific set of people know. In this context if somebody wants to count all the words in a language, it is useful to be familiar with terms such as tokens, types, lemmas, and word families. If we count the words as they appear in language, even if they are repeated, the words are called tokens. If we count all the words but not counting the repetition of a word, the words are called types. A lemma is the head word and some of its reduced and inflected forms.

Types and strategies of vocabulary learning[edit]

There are two major types of vocabulary learning: deliberate and incidental. Vocabulary learning types and low-frequency are important components in a vocabulary teaching program. The two major types of vocabulary learning are deliberate and low-frequency. It is important to treat these types as complementary -rather than mutually exclusive- by using different vocabulary learning strategies and their combinations.

Scott Thornbury (2002) describes these types by stating that «some of the words will be learned actively», while others «will be picked up incidentally» (p. 32). Dodigovic (2013) and Nation (2006) emphasize the same distinction — only using a different term for the one side of this dichotomy: deliberate vocabulary learning. Nation (2006) also adds another nuance to this concept by calling it «deliberate, decontextualized vocabulary learning» (p. 495). Elgort (2011) to uses the term deliberate, while DeCarrico (2001) prefers to talk about «explicit versus implicit learning» (p. 10). Other authors, although employing various terminology are also in favor of this same distinction. For example, throughout their article, Alemi and Tayebi (2011) talk of “incidental and intentional” vocabulary learning, as does also Hulstijn (2001). Expanding the terminology even further, Gu (2003) uses the terms “explicit and implicit learning mechanisms” throughout his article in discussing the second language learning strategies. Whatever terminology is used in the literature by different authors, the two major types of vocabulary learning are discussed: explicit and incidental. These two concepts should not be perceived as competitors but rather as mutually reinforcing (Nation, 2006b).

In both types of vocabulary learning or their combination, the efficiency of learning is achieved by following one or more of the vocabulary learning strategies. Different researchers look into the nature of this concept from various perspectives. Given that vocabulary learning strategies are very diverse, Schmitt(2000) suggests a summary of major vocabulary learning strategies and classify them into five groups: determination, social, memory, cognitive and meta-cognitive. Building on this classification, Xu and Hsu (2017) suggest two major categories of vocabulary learning strategies – direct and indirect. The first category includes four types of strategies: memory, cognitive and compensation strategies; the second category contains the meta-cognitive, effective and social strategies. Based on their research, Lawson and Hogben (1996) distinguish repetition as the major strategy of vocabulary learning, while Mokhtar et al. (2009) explain that ESL students prefer vocabulary strategies such as guessing and using a dictionary.

Deliberate Vocabulary Learning[edit]

One of the major types of vocabulary learning in language acquisition is deliberate vocabulary learning. Before moving on to presenting the literature, it is important to mention that when talking about deliberate vocabulary learning, various terminologies are used by different linguists and writers. Elgort and Warren (2014), as well as Schmitt (2000), use the term explicit (which is mostly used for grammar teaching), while Nation (2006) uses the word decontextualized vocabulary learning and contrasts the term with «learning from context» (p. 494) without explicitly using the term incidental vocabulary learning. Intentional vocabulary learning (Dodigovic, Jeaco & Wei, 2017; Hulstijn, 2001), active learning (Thornbury, 2002), and direct instruction (Lawrence et al., 2010) are also used. However, throughout this paper, the term deliberate (Elgort, 2011; Nation, 2006) will be used to refer to this concept.

The advocates of deliberate vocabulary learning paradigm -for example, Coady, 1993; Nation, 1990, 2001, as cited in Ma & Kelly, 2006- agree that context is the main source for vocabulary acquisition. However, they also believe that in order to be able to build up sufficient vocabulary and acquire the necessary strategies to handle the context when reading, learners need support. Thus, extensive reading may be sufficient for developing advanced students’ vocabulary, but it has to be supplemented with deliberate vocabulary learning at lower proficiency levels (Elgort & Warren, 2014). Kennedy (2003) supports this notion and argues that deliberate learning is more appropriate for students with up to an intermediate level of proficiency, while incidental learning, which can occur outside the classroom, is more valuable with higher proficiency students. The limited classroom time should be spent on the deliberate teaching of vocabulary (Schmitt, 2000), as the main problem of vocabulary teaching is that only a few words, or a small part of what is required to know a word, can be taught at a time (Ma & Kelly, 2006). Ma and Kelly (2006) argue that learning a word requires more “deliberate mental effort” than merely being engaged in meaning-focused activities. However, according to the authors, the advocates of deliberate approach believe that it should be combined with incidental learning to be more efficient.

Schmitt (2000) demonstrates that deliberate vocabulary learning, unlike incidental learning, is time-consuming, and too laborious. Moreover, according to Nation (2005), deliberate vocabulary learning is “one of the least efficient ways” to improve students’ vocabulary knowledge. Yet, he claims that it is a vital component in vocabulary teaching programs. However, Schmitt (2000) states that deliberate vocabulary learning gives the learners the “greatest chance” for acquiring vocabulary, as it focuses their attention directly on the target vocabulary. He presents an important concept from the field of psychology: “the more one manipulates, thinks about, and uses mental information, the more likely it is that one will retain that information” (p. 121). The deeper the processing, the more likely it is for the newly learned words to be remembered. Therefore, explicit attention should also be given to vocabulary, especially when the aim is language-focused learning (Nation, 2006b). According to Ellis (1994, as cited in Laufer & Hulstijn, 2001), while the meaning of a word requires “conscious processing” and is learned deliberately, the articulation of its form is learned incidentally because of frequent exposure. Ma and Kelly (2006) mention the necessity of establishing a link between the meaning and form of a word by various strategies, e.g., “direct memorization,” which is a strategy of deliberate vocabulary teaching.

In vocabulary teaching programs, it is also necessary to consider the frequency of the words (Nation, 2006b). Thus, high-frequency words deserve to be taught explicitly (Kennedy, 2003) and sometimes even low-frequency words can be taught and learned deliberately, for example through word cards, word part analysis, and dictionary as recommended by Nation (2006b). However, when measuring the difficulty by the results, deliberate vocabulary learning is easier than incidental learning, yet it needs more focused effort. Therefore, directing deliberate attention to the particular aspect can lighten «the learning burden» (Nation, 2006a).

To sum up, deliberate vocabulary learning is essential to reach a threshold of the vocabulary size and it is a prerequisite to incidental learning (Schmitt, 2000).

Incidental Vocabulary Learning[edit]

Another type of vocabulary learning is called incidental vocabulary learning. By its nature, incidental vocabulary learning is one of the key aspects of language acquisition. This concept, which is also referred to as passive learning (Shmidth, 1990; as cited in Alemi & Tayebi, 2011) or implicit learning (Gu, 2003), is the process of acquiring vocabulary without placing the focus on specific words to be learned (Paribakht & Wesche, 1999). It is deemed that, this type of learning should occur with low-frequency words (Nation, 2005) as the first few thousand words are better learned through deliberate learning approach (Huckin & Coady 1999). However, this may be hampered by the fact that several encounters with a word are needed before it is committed to memory (Nation, 1990), which may not be possible with low-frequency words (Nation 1990).

Aelmi and Tayebi (2011) as well as Schmitt (2000) link incidental vocabulary learning with the communicative context. The formers stress that incidental vocabulary learning occurs by «picking up structures and lexicon of a language, through getting engaged in a variety of communicative activities» (p. 82), while the latter indicates that producing language for communicational purposes results in incidental learning.

There is a number of factors which affect the occurrence of incidental vocabulary learning. Most of the scholars agree that the best way is through extensive reading (Jian-ping, 2013; Restrepo Ramos, 2015). Restrepo Ramos (2015) indicates that “there is strong evidence that supports the occurrence of incidental vocabulary learning through reading for meaning comprehension” (p. 164). However, as research shows, 95% of the words must be familiar to the reader to understand a text (Hirsh & Nation, 1992; Laufer, 1989). According to Nation (2009), this figure is even higher, i.e., 98 percent. Huckin & Coady (1999),[2] on the other hand, argue that «extensive reading for meaning does not automatically lead to the acquisition of vocabulary. Much depends on the context surrounding each word, and the nature of the learner’s attention» (p. 183). While Dodigovic (2015) finds that it is the approach that matters, i.e., the bottom-up processing of readings is better than the top-down. Thus, to develop incidental vocabulary learning, the learners should be exposed to the words in different informative contexts, following the bottom-up processing of the readings.

References[edit]

- Alemi, M., & Tayebi, A. (2011). The influence of incidental and intentional vocabulary acquisition and vocabulary strategy use on learning L2 vocabularies. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 2(1), 81-98. DOI:10.4304/jltr.2.1.

- Decarrico, J. S. (2001). Vocabulary learning and teaching. Teaching English as a second or foreign language, 3, 285-299.

- Dodigovic, M. (2013). Vocabulary learning: An electronic word card study. Perspectives 20(1). TESOL Arabia Publications.

- Dodigovic, M. (2015). How incidental is incidental vocabulary learning? In Gitsaki, C., Gobert, M., & Demirci, H. (Eds.), (pp. 203-215). *Current issues in reading, writing and visual literacy: Research and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars.

- Dodigovic, M., Jeaco, S., & Wei, R. (2017). Trends in Vocabulary Research. TESOL International Journal, 12(1), 1-6.

- Elgort, I. (2011). Deliberate Learning and Vocabulary Acquisition in a Second Language. Language Learning, 61(2), 367-413.

- Elgort, I., & Warren, P. (2014). L2 Vocabulary Learning From Reading: Explicit and Tacit Lexical Knowledge and the Role of Learner and Item Variables. Language Learning, 64(2): 365–414. DOI:10.1111/lang.12052

- Gu, P. (2003). Vocabulary learning in a second language: Person, Task, Context and Strategies. The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, 7(2). http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume7/ej26/ej26a4/?wscr

- Hirsh and Nation, P. (1992). What vocabulary size is needed to read unsimplified texts for pleasure? Reading in a Foreign Language, 8(2), 689-696.

- Huckin, T., & Coady, J. (1999). Incidental vocabulary acquisition in a second language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21(2), 181-193.

- Hulstijn, J. H. (2001). Intentional and incidental second-language vocabulary learning: A reappraisal of elaboration, rehearsal and automaticity. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and Second Language Instruction, 258-286. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jian-ping, L. (2013). Is incidental vocabulary acquisition feasible to EFL learning? English Language Teaching, 6(10), 245-251.

- Kennedy, G. (2003). Amplifier Collocations in the British National Corpus: Implications for English Language Teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 37(3), 467-487. DOI:10.2307/3588400

- Laufer, B. (1989). What percentage of text-lexis is essential for comprehension? In Lauren, Ch., & Nordman, M. (Eds.). Special language: From humans thinking to thinking machines, Multiligual Matters, 316-323

- Laufer, B. & Hulstijn, J. (2001). Incidental vocabulary acquisition in a second language: The construct of task-induced involvement. Applied Linguistics, 22(1), 1-26.

- Lawrence, J., Capotosto, L., Branum-Martin, L., White, C., & Snow, C. (2010). Language proficiency, home-language status, and English vocabulary development: A longitudinal follow-up of the Word Generation program. Unpublished manuscript, Harvard University.

- Lawson, M., & Hogben, D. (1996). The vocabulary-learning strategies of foreign-language students. Language Learning, 46(1), 101-135.

- Ma, Q., & Kelly, P. (2006). Computer assisted vocabulary learning: Design and evaluation. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 19(1), 15-45.

- Mokhtar, A., Rawian, R., Yahaya, M., Abdullah, A., & Mohamed, A. (2009). Vocabulary learning strategies of adult ESL learners. The English Teacher, 38, 133-145.

- Nation, P. (1990). Teaching and learning vocabulary. Boston, MA: Heinle and Heinle.

- Nation, P. (2005) Teaching vocabulary. Asian EFL Journal.

- Nation, P. (2006a). Vocabulary: Second language. In K. Brown (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Language and Linguistics, 2nd Ed. Oxford: Elsevier, 6, 448-454.

- Nation, P. (2006b). Language education — vocabulary. In K. Brown (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Language and Linguistics, 6, 2nd Ed. Oxford: Elsevier, 494-499.

- Nation, P. (2009). Teaching ESL/EFL reading and writing. New York: Routledge.

- Pariribakht, T., & Wesche, M. (1999). Reading and ‘incidental’ L2 vocabulary acquisition: An introspective study of lexical referencing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21(1), 195-224.

- Restrepo Ramos, F. D. (2015). I ncidental vocabulary learning in second language acquisition: A literature review. PROFILE: Issues In Teachers’ Professional Development, 17(1), 157-166.

- Schmitt, N. (2000). Vocabulary in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thornbury, S. (2002). How to teach vocabulary. Edinburgh Gate: Pearson Education Limited.

- Xu, X., & Hsu, W-Ch. (2017). A new inventory of vocabulary learning strategy for Chinese tertiary EFL learners. TESOL International Journal, 12(1), 7-31.

Specific

- ^ Nation, I.S.P (2000). Learning Vocabulary in another Language. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Huckin, Thomas; Coady, James (June 1999). «INCIDENTAL VOCABULARY ACQUISITION IN A SECOND LANGUAGE: A Review». Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 21 (2): 181–193. doi:10.1017/S0272263199002028. ISSN 1470-1545. S2CID 145288413.

Phonics is a type of language instruction that involves breaking words down into their parts. It helps children learn to code and decode language in written words.

The codes of our language are phonemes (spoken sounds) and their associated graphemes (the letter combinations that represent sounds).

Children need to learn all 44 phonemes and graphemes in the English language so they can decipher language and, therefore, read!

Phonics is the dominant method of teaching reading around the world.

There are four major types of phonics:

- Synthetic phonics

- Analogy phonics

- Analytic phonics

- Embedded phonics

Want to Learn how to Teach Phonics?

If you need some guidance on how to teach phonics, it might be worthwhile getting a guidebook for parents. I love this Phonics from A to Z Practical Guide by Wiley Blevins.

Check the Price on Amazon

Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Read Also: 7 Best Toys for Teaching Phonics

1. Synthetic Phonics

Quick Summary: Focuses on explicit instruction of phonemes and blending them to construct words. It is the most direct and structured method of phonics.

Also known as: Direct Phonics

Synthetic phonics starts with teaching phonemes and then progresses to teaching full words. It always starts with systematically teaching phonics beginning with explicit instruction about the 44 phonemes and graphemes in the English language. This first stage of instruction usually involves whole-class explicit teaching lessons and a great deal of repetition of phonemes.

As children progress, educators focus on blending phonemes to build words. Synthetic phonics therefore often gets the nickname of the ‘blending and building’ approach.

Synthetic phonics is the compulsory mode of phonics teaching in England, Australia, Germany and Austria (Machin, McNally & Viaregno, 2018).

How Synthetic Phonics is Taught:

Students quickly learn all 44 phonemes through whole-class direct instruction. The phonemes and graphemes are taught in isolation, not as parts of words.

As students become more competent with each phoneme, the teacher creates structured lessons that involve blending phonemes to create full words.

For example, if students know the basic single-letter phonemes (a, b, c, d, e, etc.) and some basic two-letter phonemes (at, it, ing), they can start blending them to form words like: cat, mat, fat, hat, sat.

Pros

- Structure: It provides a very structured introduction to reading. This structure ensures no phonemes or graphemes are missed and students get thorough instruction.

- Good for Manipulating Language: The focus on blending and building words using phonemes helps children when they come across (or need to write) unfamiliar words. They will be very used to the process of blending phonemes to create words.

- Research Backed: Research consistently finds it to be the most effective method of teaching reading.

Cons

- Whole Class: Learning of phenomes and graphemes tends to be done through whole-class instruction rather than differentiated and individualized.

- Decontextualized: Phonemes and graphemes are learned out of context and disconnected to words. This may confuse students and make them unsure about the purpose of the lesson.

2. Analytic Phonics

Quick Summary: Focuses on deconstructing words to identify phonemes. Starts with familiar words and breaks them down into their parts.

Also known as: Implicit or Integrated Phonics

Analytic phonics starts with familiar words that students have learned by rote. Lessons then involve having the students decode and break down those words into their phonemes. Usually, the words that are analyzed have a beginning phoneme (onset) and an ending phoneme (rime).

Machin, McNally and Viaregno (2018) define analytic phonics this way:

“Analytic phonics does not involve learning the sounds of letters in isolation. Instead, children are taught to recognize the beginning and ending sounds of words, without breaking these down into the smallest constituent sounds.” (Machin, McNally & Viaregno, 2018, p. 221)

This approach is distinct from the synthetic approach because in the analytic approach phonemes are not taught in isolation. Further, the synthetic phonics approach of ‘blending’ phonemes to ‘build’ words is non-existent.

In short, the focus is on deconstructing language to identify patterns rather than constructing it.

How Analytic Phonics is Taught:

A teacher will present the familiar words, e.g: mat, fat, cat, hat, rat. The students then try to identify the phoneme ‘at’ within those words.

The teacher will then give children many, many examples of words that share a common phoneme / grapheme that is being taught. Through examples, the children will come to identify or ‘discover’ patterns in written language that helps them become more effective readers. The wide variety of examples can help children understand and get that ‘lightbulb moment’.

Pros

- Teaches Sounds in Context: Sounds are learned as parts of words, rather than in isolation and decontextualized.

- Starts with the Familiar: Teachers can start with words children are familiar with and use them as a springboard for further teaching.

- Helps with Decoding New Words: While the synthetic method is all about encoding, the analytic method emphasizes decoding, which is great for reading new and unfamiliar words.

Cons

- Uses Guess Work: Children often get away with guessing phonemes (and at times are encouraged to). They will know either the onset or rime, and guess the rest of the word rather than focusing fully on all phonemes in the word.

- Some Students Slip Behind: Because instruction is not as structured and direct as in the synthetic approach, some struggling students could slip behind and not understand.

- Not as Good for Constructing Words: The focus of this approach is on deconstructing rather than constructing words.

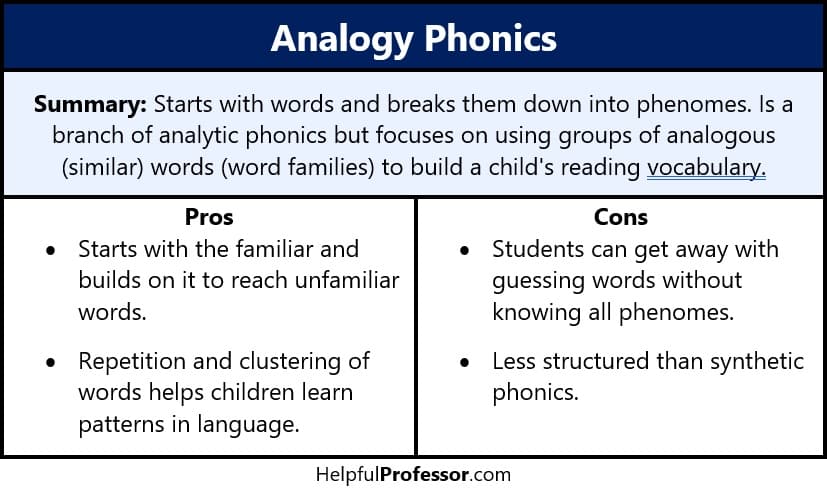

3. Analogy Phonics

Quick Summary: An approach to phonics that relies on using groups of analogous (similar) words to build a child’s reading vocabulary.

Analogy phonics is in reality just a form of analytic phonics. They both focus on whole words and then deconstruct them into their phoneme / grapheme parts.

What sets analogy phonics apart is that it attempts to build a child’s vocabulary of known words by introducing words that are analogous (similar). For example, a child knows the word ‘sing’ so you can by extension teach them the word ‘ring’.

Teachers will often create word families and focus on words within that word family – trying to build up that word family with as many words as possible.

How Analogy Phonics is Taught:

In my classroom, one word family that I work on is the ‘ing sisters’. The ing sisters are three words that get along and make the sound ‘ing’. We will talk all about the word sing and what it means. Then, I will extend the lesson out to learn other ‘ing’ words like ring, king, thing, cling, ping, bring.

Pros

- Builds a Child’s Vocabulary: Starts with the familiar and builds on it to reach unfamiliar or less well-known words.

- Helps Children Identify Patterns: The repetition and clustering of words helps children learn patterns in the English language.

Cons

- Uses Guess Work: Children often get away with guessing phonemes (and at times are encouraged to). They will know either the onset or rime, and guess the rest of the word rather than focusing fully on all phonemes in the word.

- Not as Good for Constructing Words: The focus of this approach is on deconstructing rather than constructing words.

4. Embedded Phonics

Quick Summary: Focuses on teaching phonics in authentic contexts. Lessons begin with a teacher reading a book and identifying teachable moments.

Also known as: Incidental Phonics

Embedded phonics involves teaching phonemes and graphemes when they arise in teachable moments in books. It focuses on learning to decode language during reading tasks, rather than through structured lessons. It emphasizes the importance of learning through context and ongoing exposure to words.

The embedded approach is often used as part of the whole language learning method, a largely defunct approach to teaching reading. Nonetheless, it remains a very valuable approach for teachers to use, especially when working one-to-one with a learner.

How Embedded Phonics is Taught:

At the start of an embedded phonics module, the teacher will do most or all of the reading. They will stumble upon phonemes / graphemes that are interesting or recur in the reading session and teach the children about them within the context of the reading session.

As children become more competent, the teacher will gradually release responsibility to the child. Teachers may sit with a child who is reading a text, and when the child comes across a difficult word, the teacher will use it as an opportunity to teach about the phoneme / grapheme that is of concern.

Pros

- Contextualized: Students learn about words and how to decode them while reading actual books. They can use images and surrounding sentences to infer what a word might be.

- Good for Practice: Once children have learned the basics of phonics, they need a lot of practice – and when they stumble upon issues, they need reinforcement on those issues. This is where embedded phonics is helpful.

Cons

- Guess Work: When students look at context to understand a word, they are guessing rather than thinking about phonetics.

- Can’t be Used in Isolation: It won’t work alone – at some point students need direct explicit and structured instruction.

Read Also: Best Toys for Learning Spelling & Writing

Conclusion

The different methods of phonics are differentiated on two axes: contextualization (learning phenomes in relation to words and texts, or as decontextualized sounds) and structured instruction (clear direct lessons vs. incidental learning). Synthetic phonics is the most structured but least contextualized method. Embedded phonics is the least structured but most contextualized method:

Phonics is widely regarded as the best way to teach reading to a child. While most large-scale studies highlight that synthetic phonics is the most effective method, many educators believe all four types of phonics should be used in different contexts in the classroom for an integrated and holistic reading instruction approach. Some children may find that they have that ‘lightbulb moment’ from one of the other approaches. In particular, many believe educators should start with synthetic phonics and introduce other methods (analytic, analogy and embedded) phonics after the basics have been learned.

Read Also: The Importance of Reading & its Impact on your Future Success

References

Machin, S., McNally, S., & Viarengo, M. (2018). Changing how literacy is taught: evidence on synthetic phonics. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 10(2), 217-41. Retrieved from: http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/846338/1/pol.20160514.pdf

Torgerson, C., Brooks, G., Gascoine, L., & Higgins, S. (2019). Phonics: reading policy and the evidence of effectiveness from a systematic ‘tertiary’review. Research Papers in Education, 34(2), 208-238.

Johnston, R. S., McGeown, S., & Watson, J. E. (2012). Long-term effects of synthetic versus analytic phonics teaching on the reading and spelling ability of 10 year old boys and girls. Reading and Writing, 25(6), 1365-1384. Retrieved from: https://hull-repository.worktribe.com/preview/464932/Long.pdf

Johnston, R., & Watson, J. (2005). The effects of synthetic phonics teaching on reading and

spelling attainment: A seven year longitudinal study. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Education Department.

Patrick, C. J. (2018). Developmentally appropriate spelling and phonics instruction and its impact on student level of orthography, decoding ability, and reading accuracy (Doctoral dissertation, Wittenberg University). Retrieved from: https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=witt1534160012802077&disposition=inline

Glossary of Terms

Phonics: A way of teaching students how to read. Its focus is on connecting sounds (phonemes) to their graphical representation as letters (graphemes).

Phonemes: The basic sounds that make up the English language.

Graphemes: The basic word combinations that refer to sounds (such as ‘oo’, ‘ee’, ‘bl’, ‘cr’, etc.)

Onset and Rime: The onset is the first phoneme in a word, the rime is the final phoneme in a word.

Consonant blend: Consonant blends are two or more consonants together that make a blend of two sounds. They are sounds like ‘bl, br, cl, dr, fr, tr, fl’.

Consonant digraph: Consonant digraphs are two or more consonants together that make one sound. They are sounds like ‘wh, sh, ch, th, ph’.

Vowel Digraph: Vowel digraphs are two or more vowels together that make one sound, like ‘oo, ee, oa’.

Trigraph: Trigraphs are three or more letters together that create one sound, like ‘ing, ugh, ate, ure, ear, igh’.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education.

Vocabulary instruction

Vocabulary refers to the words we must know to communicate effectively. In general, vocabulary can be described as oral vocabulary or reading vocabulary. Oral vocabulary refers to words that we use in speaking or recognize in listening. Reading vocabulary refers to words we recognize or use in print.

Vocabulary plays an important part in learning to read. As beginning readers, children use the words they have heard to make sense of the words they see in print. Consider, for example, what happens when a beginning reader comes to the word dig in a book. As she begins to figure out the sounds represented by the letters d, i, g, the reader recognizes that the sounds make up a very familiar word that she has heard and said many times. Beginning readers have a much more difficult time reading words that are not already part of their oral vocabulary.

Vocabulary also is very important to reading comprehension. Readers cannot understand what they are reading without knowing what most of the words mean. As children learn to read more advanced texts, they must learn the meaning of new words that are not part of their oral vocabulary.

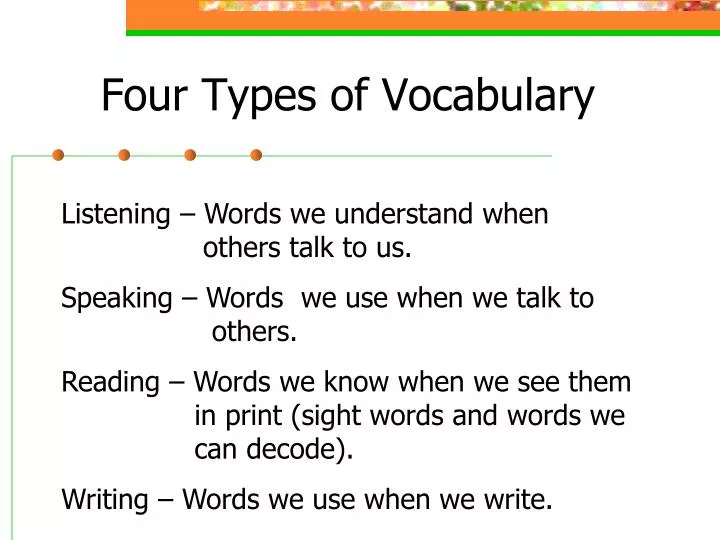

Types of vocabulary

Researchers often refer to four types of vocabulary

listening vocabulary-the words we need to know to understand what we hear.

speaking vocabulary-the words we use when we speak.

reading vocabulary-the words we need to know to understand what we read.

writing vocabulary-the words we use in writing.

What does scientifically-based research tell us about

vocabulary instruction?

The scientific research on vocabulary instruction reveals that (1) most vocabulary is learned indirectly, and (2) some vocabulary must be taught directly. The following conclusions about indirect vocabulary learning and direct vocabulary instruction are of particular interest and value to classroom teachers:

Children learn the meanings of most words indirectly, through everyday experiences with oral and written language.

Children learn word meanings indirectly in three ways:

They engage daily in oral language.

Young children learn word meanings through conversations with other people, especially adults. As they engage in these conversations, children often hear adults repeat words several times. They also may hear adults use new and interesting words. The more oral language experiences children have, the more word meanings they learn.

They listen to adults read to them.

Children learn word meanings from listening to adults read to them. Reading aloud is particularly helpful when the reader pauses during reading to define an unfamiliar word and, after reading, engages the child in a conversation about the book. Conversations about books help children to learn new words and concepts and to relate them to their prior knowledge and experience.

They read extensively on their own.

Children learn many new words by reading extensively on their own. The more children read on their own, the more words they encounter and the more word meanings they learn.

Indirect vocabulary learning

Students learn vocabulary

indirectly when they hear and see words used in many different contexts-for example, through conversations with adults, through being read to, and through reading extensively on their own.

Direct vocabulary learning

Students learn vocabulary

directly when they are explicitly taught both individual words and word-learning strategies. Direct vocabulary instruction aids reading comprehension.

Specific Word Instruction

Word Learning Instruction

Although a great deal of vocabulary is learned indirectly, some vocabulary should be taught directly.

Direct instruction helps students learn difficult words, such as words that represent complex concepts that are not part of the students’ everyday experiences. Direct instruction of vocabulary relevant to a given text leads to a better reading comprehension.

Direct instruction includes:

(1) providing students with specific word instruction; and

(2) teaching students word-learning strategies.

Specific word instruction

Specific word instruction, or teaching individual words, can deepen students’ knowledge of word meanings. In-depth knowledge of word meanings can help students understand what they are hearing or reading. It also can help them use words accurately in speaking and writing.

In particular:

Teaching specific words before reading helps both vocabulary learning and reading comprehension.

Before students read a text, it is helpful to teach them specific words they will see in the text. Teaching important vocabulary before reading can help students both learn new words and comprehend the text.Extended instruction that promotes active engagement with vocabulary improves word learning.

Children learn words best when they are provided with instruction over an extended period of time and when that instruction has them work actively with the words. The more students use new words and the more they use them in different contexts, the more likely they are to learn the words.Repeated exposure to vocabulary in many contexts aids word learning.

Students learn new words better when they encounter them often and in various contexts. The more children see, hear, and work with specific words, the better they seem to learn them. When teachers provide extended instruction that promotes active engagement, they give students repeated exposure to new words. When the students read those same words in their texts, they increase their exposure to the new words.

An example of classroom instruction

Teaching specific words: A teacher plans to have his third-grade class read the novel Stone Fox, by John Reynolds Gardiner. In this novel, a young boy enters a dogsled race in hopes of winning prize money to pay the taxes on his grandfather’s farm. The teacher knows that understanding the concept of taxes is important to understanding the novel’s plot. Therefore, before his students begin reading the novel, the teacher may do several things to make sure that they understand what the concept means and why it is important to the story. For example, the teacher may:

- engage students in a discussion of the concept of taxes; and/or

- read a sentence from the book that contains the word taxes and ask students to use context and their prior knowledge to try to figure out what it means.

To solidify their understanding of the word, the teacher might ask students to use taxes in their own sentences.

Word learning strategies

Of course, it is not possible for teachers to provide specific instruction for all the words their students do not know. Therefore, students also need to be able to determine the meaning of words that are new to them but not taught directly to them. They need to develop effective word-learning strategies. Word-learning strategies include:

(1) how to use dictionaries and other reference aids to learn word meanings and to deepen knowledge of word meanings;

(2) how to use information about word parts to figure out the meanings of words in text; and

(3) how to use context clues to determine word meanings.

Using dictionaries and other reference aids. Students must learn how to use dictionaries, glossaries, and thesauruses to help broaden and deepen their knowledge of words, even though these resources can be difficult to use. The most helpful dictionaries include sentences providing clear examples of word meanings in context.

An example of classroom instruction

Extended and active engagement with vocabulary

A first-grade teacher wants to help her students understand the concept of jobs, which is part of her social studies curriculum. Over a period of time, the teacher engages students in exercises in which they work repeatedly with the meaning of the concept of jobs. The students have many opportunities to see and actively use the word in various contexts that reinforce its meaning.

The teacher begins by asking the students what they already know about jobs and by having them give examples of jobs their parents have. The class might have a discussion about the jobs of different people who work at the school.

The teacher then reads the class a simple book about jobs. The book introduces the idea that different jobs help people meet their needs, and that jobs either provide goods or services. The book does not use the words goods and services, rather it uses the verbs makes and helps.

The teacher then asks the students to make up sentences describing their parents’ jobs by using the verbs makes and helps (e.g., «My mother is a doctor. She helps sick people get well.»)

Next, the teacher asks students to brainstorm other jobs. Together, they decide whether the jobs are «making jobs» or «helping jobs.» The job names are placed under the appropriate headings on a bulletin board. They might also suggest jobs that do not fit neatly into either category.

The teacher might then ask the students to share whether they think they would like to have a making or

a helping job when they grow up.

The teacher next asks the students to talk with their parents about jobs. She tells them to try to bring to class two new examples of jobs-one making job and one helping job.

As the students come across different jobs throughout the year (for example, through reading books, on field trips, through classroom guests), they can add the jobs to the appropriate categories on the bulletin board.

Repeated exposure to words: A second-grade class is reading a biography of Benjamin Franklin. The biography discusses Franklin’s important role as a scientist. The teacher wants to make sure that her students understand the meaning of the words science and scientist, both because the words are important to understanding the biography and because they are obviously very useful words to know in school and in everyday life.

At every opportunity, therefore, the teacher draws her students’ attention to the words. She points out the words scientist and science in textbooks and reading selections, particularly in her science curriculum. She has students use the words in their own writing, especially during science instruction.

She also asks them to listen for and find in print the words as they are used outside of the classroom-in newspapers, magazines, at museums, in television shows or movies, or the Internet.

Then, as they read the biography, she discusses with students in what ways Benjamin Franklin was a scientist and what science meant in his time.

An example of classroom instruction

Using word parts. Knowing some common prefixes and suffixes (affixes), base words, and root words can help students learn the meanings of many new words. For example, if students learn just the four most common prefixes in English (un-, re-, in-, dis-), they will have important clues about the meaning of about two thirds of all English words that have prefixes. Prefixes are relatively easy to learn because they have clear meanings (for example, un- means not and re- means again); they are usually spelled the same way from word to word; and, of course, they always occur at the beginnings of words.

Learning suffixes can be more challenging than learning prefixes. This is because some suffixes have more abstract meanings than do prefixes. For example, learning that the suffix -ness means «the state or quality of» might not help students figure out the meaning of kindness. Other suffixes, however, are more helpful.

For example, -less, which means «without» (hopeless, thoughtless); and -ful, which means «full of» (hopeful, thoughtful). Latin and Greek word roots are found commonly in content-area school subjects, especially in the subjects of science and social studies. As a result, Latin and Greek word parts form a large proportion of the new vocabulary that students encounter in their content-area textbooks. Teachers should teach the word roots as they occur in the texts students read. Furthermore, teachers should teach primarily those root words that students are likely to see often.

An example of classroom instruction

Using dictionaries and other reference aids:

As his class reads a text, a second-grade teacher discovers that many of his students do not know the meaning of the word board, as in the sentence, «The children were waiting to board the buses.» The teacher demonstrates how to find board in the classroom dictionary, showing students that there are four different definitions for the word. He reads the definitions one at a time, and the class discusses whether each definition would fit the context of the sentence. The students easily eliminate the inappropriate definitions of board, and settle on the definition, «to get on a train, an airplane, a bus, or a ship.»

The teacher next has students substitute the most likely definition for board in the original sentence to verify that it is «The children were waiting to get on the buses» that makes the best sense.

Word parts

Word parts include affixes (prefixes and suffixes), base words, and word roots.

Affixes are word parts that are «fixed to» either the beginnings of words (prefixes) or the ending of words (suffixes). The word disrespectful has two affixes, a prefix (dis-) and a suffix (-ful).

Base words are words from which many other words are formed.

For example, many words can be formed from the base word migrate: migration, migrant, immigration, immigrant, migrating, migratory.

Word roots are the words from other languages that are the origin of many English words.

About 60% of all English words have Latin or Greek origins.

Using word parts:

- A second-grade teacher wants to teach her students how to use the base word play as a way to help them think about the meanings of new words they will encounter in reading. To begin, she has students brainstorm all the words or phrases they can think of that are related to play. The teacher records their suggestions: player, playful, playpen, ballplayer, and playing field. Then she has the class discuss the meaning of each of their proposed words and how it relates to play.

- A third-grade teacher identifies the base word note. He then sets up a «word wall,» and writes the word note at the top of the wall. As his students read, the teacher has them look for words that are related to note and add them to the wall. Throughout their reading, they gradually add to the wall the words notebook, notation, noteworthy, and notable.

An example of classroom instruction

Using context clues. Context clues are hints about the meaning of an unknown word that are provided in the words, phrases, and sentences that surround the word. Context clues include definitions, restatements, examples, or descriptions. Because students learn most word meanings indirectly, or from context, it is important that they learn to use context clues effectively.

Not all contexts are helpful, however. Some contexts give little information about a word’s meaning. An example of an unhelpful context is the sentence, «We heard the back door open, and then recognized the buoyant footsteps of Uncle Larry.» A number of possible meanings of buoyant could fit this context, including heavy, lively, noisy, familiar, dragging, plodding, and so on. Instruction in using context clues as a word-learning strategy should include the idea that some contexts are more helpful than others.

An example of classroom instruction

Using context clues: In a third-grade class, the teacher models how to use context clues to determine word meanings as follows:

Student (reading the text): When the cat pounced on the dog, the dog jumped up, yelping, and

knocked over a lamp, which crashed to the floor. The animals ran past Tonia, tripping her. She fell to the floor and began sobbing. Tonia’s brother Felix yelled at the animals to stop. As the noise and confusion mounted, Mother hollered upstairs, «What’s all that commotion?«Teacher: The context of the paragraph helps us determine what commotion means. There’s yelping and crashing, sobbing, and yelling. And then the last sentence says, «as the noise and confusion mounted.» The author’s use of the words noise and confusion gives us a very strong clue as to what commotion means. In fact, the author is really giving us a definition there, because commotion means something that’s noisy and confusing-a disturbance. Mother was right; there was definitely a commotion!

Questions you may have about

vocabulary instruction

How can I help my students learn words indirectly?

You can encourage indirect learning of vocabulary in two main ways. First, read aloud to your students, no matter what grade you teach. Students of all ages can learn words from hearing texts of various kinds read to them. Reading aloud works best when you discuss the selection before, during, and after you read. Talk with students about new vocabulary and concepts and help them relate the words to their prior knowledge and experiences.

The second way to promote indirect learning of vocabulary is to encourage students to read extensively on their own. Rather than allocating instructional time for independent reading in the classroom, however, encourage your students to read more outside of school. Of course, your students also can read on their own during independent work time in the classroom-for example, while you teach another small group or after students have completed one activity and are waiting for a new activity to begin.

What words should I teach?

You won’t be able to directly teach your students all the words in a text that they might not already know. In fact, there are several reasons why you should not directly teach all unknown words.

- The text may have a great many words that are unknown to students-too many for direct instruction.

- Direct vocabulary instruction can take a lot of class time-time that you might better spend on having your students read.

- Your students can understand most texts without knowing the meaning of every word in the text.

- Your students need opportunities to use word-learning strategies to learn on their own the meanings of unknown words.

You will probably to be able to teach thoroughly only a few new words (perhaps eight or ten) per week, so you need to choose the words you teach carefully. Focus on teaching three types of words:

Important words. When you teach words before students read a text, directly teach those words that are important for understanding a concept or the text. Your students might not know several other words in the selection, but you will not have time to teach them all. Of course, you should prepare your students to use word-learning strategies to figure out the meanings of other words in the text.

Useful words. Teach words that students are likely to see and use again and again. For example, it is probably more useful for students to learn the word fragment than the word fractal; likewise, the word revolve is more useful than the word gyrate.

Difficult words. Provide some instruction for words that are particularly difficult for your students.

Words with multiple meanings are particularly challenging for students. Students may have a hard time understanding that words with the same spelling and/or pronunciation can have different meanings, depending on their context. Looking up words with multiple meanings in the dictionary can cause confusion for students. They see a number of different definitions listed, and they often have a difficult time deciding which definition fits the context. You will have to help students determine which definition they should choose.

Idiomatic expressions also can be difficult for students, especially for students who are English language learners. Because idiomatic expressions do not mean what the individual words usually mean, you often will need to explain to students expressions such as «hard hearted,» «a chip off the old block,» «drawing a blank,» or «get the picture.»

| Multiple-meaning words that can be difficult for students: | Examples |

| Words that are spelled the same but are pronounced differently |

sow (a female pig); sow (to plant seeds) bow (a knot with loops); bow (the front of a ship) |

| Words that are spelled and pronounced the same, but have different meanings |

mail (letters, cards, and packages); mail (a type of armor) ray (a narrow beam of light); ray (a type of fish); ray (part of a line) |

How well do my students need to «know» vocabulary words?

Students do not either know or not know words. Rather, they know words to varying degrees. They may never have seen or heard a word before. They may have heard or seen it, but have only a vague idea of what it means. Or they may be very familiar with the meaning of a word and be able to use it accurately in their own speech and writing. These three levels of word knowledge are called unknown, acquainted, and established.

As they read, students can usually get by with some words at the unknown or acquainted levels. If students are to understand the text fully, however, they need to have an established level of knowledge for most of the words that they read.

| Level of Word Knowledge | Definition |

| Unknown | The word is completely unfamiliar and its meaning is unknown. |

| Acquainted | The word is somewhat familiar; the student has some idea of its basic meaning. |

| Established | The word is very familiar; the student can immediately recognize its meaning and use the word correctly. |

Are there different types of word learning?

If so, are some types of learning more difficult than others?

Four different kinds of word learning have been identified:

- learning a new meaning for a known word;

- learning the meaning for a new word representing a known concept;

- learning the meaning of a new word representing an unknown concept; and

- clarifying and enriching the meaning of a known word.

These types vary in difficulty. One of the most common, yet challenging, is the third type: learning the meaning of a new word representing an unknown concept. Much of learning in the content areas involves this type of word learning. As students learn about deserts, hurricanes, and immigrants, they may be learning both new concepts and new words. Learning words and concepts in science, social studies, and mathematics is even more challenging because each major concept often is associated with many other new concepts. For example, the concept deserts is often associated with other concepts that may be unfamiliar, such as cactus, plateau, and mesa.

| Type of word Learning | Explanation |

| Learning a new meaning for a known word | The student has the word in her oral or reading vocabulary, but she is learning a new meaning for it. For example, the student knows what a branch is,and is learning in social studies about both branches of rivers and branches of government. |

| Learning the meaning for a new word representing a known concept | The student is familiar with the concept but he does not know the particular word for that concept. For example, the student has had a lot of experience with baseballs and globes, but does not know that they are examples of spheres. |

| Learning the meaning of a new word representing an unknown concept | The student is not familiar with either the concept or the word that represents that concept, and she must learn both. For example, the student may not be familiar with either the process or the word photosynthesis. |

| Clarifying and enriching the meaning of a known word | The student is learning finer, more subtle distinctions, or connotations, in the meaning and usage of words. For example, he is learning the differences between running, jogging, trotting, dashing, and sprinting. |

What else can I do to help my students develop vocabulary?

Another way you can help your students develop vocabulary is to foster word consciousness-an awareness of and interest in words, their meanings, and their power. Word-conscious students know many words and use them well. They enjoy words and are eager to learn new words-and they know how to learn them.

You can help your students develop word consciousness in several ways. Call their attention to the way authors choose words to convey particular meanings. Encourage students to play with words by engaging in word play, such as puns or palindromes. Help them research a word’s origin or history. You can also encourage them to search for examples of a word’s usage in their everyday lives.

Summing up

Vocabulary refers to

- the words we must know to communicateeffectively.

- Oral vocabulary refers to words that we use in speaking or recognize in listening.

- Reading vocabulary refers to words we recognize or use in print.

Vocabulary is important because

- beginning readers use their oral vocabulary to make sense of the words they see in print.

- readers must know what most of the words mean before they can understand what they are reading.

Vocabulary can be developed

- indirectly, when students engage daily in oral language, listen to adults read to them, and read extensively on their own.

- directly, when students are explicitly taught both individual words and word learning strategies.

Download

Skip this Video

Loading SlideShow in 5 Seconds..

Four Types of Vocabulary PowerPoint Presentation

Download Presentation

Four Types of Vocabulary

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — E N D — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Presentation Transcript

-

Four Types of Vocabulary Listening – Words we understand when others talk to us. Speaking – Words we use when we talk to others. Reading – Words we know when we see them in print (sight words and words we can decode). Writing – Words we use when we write.

-

Language Statistics • The number of words heard by children ages 1-3 • Welfare Households – 10 million • Working Class Households – 20 million • Professional Households – 30 million • (Graves & Slater, 1987)

-

Research on Vocabulary • Vocabulary knowledge is one of the best indicators of verbal ability, reading achievement and success in school. • Vocabulary difficulty strongly influences the readability of text. • Teaching vocabulary of a selection can improve students’ comprehension of that selection. (Beck, et al. 1992).

-

Research on Vocabulary • Growing up in poverty can seriously restrict the vocabulary that children learn before beginning school and makes attaining an adequate vocabulary a challenging task. • Disadvantaged students are likely to have substantially smaller vocabularies than their more advantaged peers. (Graves & Slater, 1987).

-

Research on Vocabulary • Lack of vocabulary can be a crucial factor underlying the school failure of disadvantaged students. • Students learn approximately 3,000 to 4,000 words each year, accumulating a reading vocabulary of approximately 18,000 words by the end of elementary school and 40,000 words by the end of high school. (Smith, 1941).

-

Research on Vocabulary • Some students learn an average of 8 words per day. Others learn as little as one or two. • Words can be known at different levels of understanding. • Directly teaching word meanings does not adequately reduce the gap between students with poor versus rich vocabularies. It is crucial for students to learn strategies for learning word meanings independently. (Miller, 1978).

-

Research on Vocabulary • The development of strong reading skills is the most effective word learning strategy available. However, those students who are in greatest need of vocabulary acquisition interventions tend to be the same students who read poorly and fail to engage in the amount of reading necessary to learn large numbers of words. [Matthew Effect] (Beck, et al. 2002).

-

When teaching vocabulary, DO • Teach new subject matter vocabulary in context BEFORE students’ initial reading of the new material. • Explain words in terms of relationships –word families, structural analysis, roots and affixes • Constantly direct students’ attention to the power of words and nuances of meaning

-

Vocabulary • Implicit vocabulary acquisition • When students engage in rich extensive oral interactions • When students are read to • When students read and discuss what they’ve read • Explicit vocabulary acquisition • Vocabulary activities specifically designed to teach new words

-

Vocabulary • Explicit vocabulary strategies • Use information and narrative texts • Promote thinking and extend discourse • Encourage use of novel words • Access to print • Semantic mapping • Teach word parts • Teach word origin (older students) • Use graphic organizers

-

When teaching vocabulary, DO NOT • Rely solely on incidental approaches; but avoid drill. • Teach roots, affixes in isolation. • Make definitions more difficult than the words to be defined. • Forget the different ways of approaching definitions – analogies, synonyms, antonyms, etc.

-

DICTIONARY DEFINITIONS • Do not give students lists of words to look up in a dictionary under the guise of vocabulary instruction. • This is only dictionary work, not vocabulary instruction. • Students learn the words for the test only.

-

DICTIONARY DEFINITIONS • Scott and Nagy (1997) report the results of many research studies that show that students cannot use conventional definitions to learn words. • Example from dictionary: redress – set right, remedy. “King Arthur tried to redress wrongs in his kingdom” • Student writes: “The redress for getting well when you’re sick is to stay in bed.”

-

Dictionary Definitions • Weak Differentiation • Vague Language • A More Likely Interpretation • Multiple Pieces of Information

-

Bringing Words to Life by Isabel Beck, Margaret McKeown, and Linda Kucan Three Tiers of Vocabulary Tier One *Rarely require instructional attention *Consist of basic words *Examples: baby, clock, happy, walk, jump, hop, slide, girl, boy, dog

-

Bringing Words to Life by Isabel Beck, Margaret McKeown, and Linda Kucan Three Tiers of Vocabulary Tier Three *Made of words whose frequency of use is quite low and often limited to specific domains. *Best learned when a specific need arises *Examples: isotope, lathe, peninsula, refinery

-

Bringing Words to Life by Isabel Beck, Margaret McKeown, and Linda Kucan Three Tiers of Vocabulary Tier Two *Contain high frequency words that are found across a variety of domains *Have a powerful impact on verbal functioning *Must be words students have ways to express the meaning of the word. *Examples: coincidence, absurd, industrious, merchant

-

Bringing Words to Life by Isabel Beck, Margaret McKeown, and Linda Kucan Three Tiers of Vocabulary Selecting Tier Two Words *Is it a useful word? *Will the student encounter it again? *Does the word relate to other words or ideas? *Will it enhance further learning?

-

Lesson Plan for Tier Two WordsRead the following third/fourth grade paragraph. Johnny Harrington was a kind master who treated his servants fairly. He was also a successful wool merchant and his business required that he travel often. While he was gone, his servants would tend to the fields and maintain the upkeep of his mansion. They performed their duties happily, for they felt fortunate to have such a benevolent and trusting master. (Kohnke, 2001)

-

Lesson Plan for Tier Two Words • Work with a partner to do this activity. • Read the paragraph and identify 5 Tier Two words. (Reminder: Tier Two words are words that students should have an understanding of their meaning.) • Make a list of your 5 words and define them using vocabulary that a student would use.

-

For thousands of years, sinuous strips of bituminous coal have lain beneath the wooded hills and valleys of Somerset County, Pennsylvania. Coal lured immigrants to the area in the 1800’s, and helped forge their reputation for hard work and hard living. For generations, men have earned their livelihoods—and all too often have lost their lives—in the mines’ dark confines. (Reader’s Digest, “Nine Alive! Inside the Amazing Mine Rescue”, November 2002, pg. 164)

-

Word Knowledge Continuum(Beck, et.al)

We all experience the world in unique ways, and with that comes variation in the ways we learn best. Understanding these different types of learning styles can drastically impact the way teachers handle their students, set up group projects and adapt individual learning. Without understanding and acknowledging these different ways of learning, teachers might end up with a handful of students lagging behind their classmates—in part because their unique learning style hasn’t been activated.

Part of your responsibility as an educator is to adjust your lessons to the unique group of students you are working with at any given time. The best teachers can cater to each student’s strengths, ensuring they are truly grasping the information.

So how do you meet the needs of different types of learners in your class? Join us as we outline the four types of learning styles and how teachers can practically apply this information in their classrooms.

Ways of learning: A closer look at 4 learning styles

Learning styles and preferences take on a variety of forms—and not all people fit neatly into one category. But generally speaking, these are the most common types of learners:

1. Visual learners

How to recognize visual learners in your class: Someone with a preference for visual learning is partial to seeing and observing things, including pictures, diagrams, written directions and more. This is also referred to as the “spatial” learning style. Students who learn through sight understand information better when it’s presented in a visual way. These are your doodling students, your list makers and your students who take notes.

How to cater to visual learners: The whiteboard or smartboard is your best friend when teaching these types of learners. Give students opportunities to draw pictures and diagrams on the board, or ask students to doodle examples based on the topic they’re learning. Teachers catering to visual learners should regularly make handouts and use presentations. Visual learners may also need more time to process material, as they observe the visual cues before them. So be sure to give students a little time and space to absorb the information.

2. Auditory learners

How to recognize auditory learners in your class: Auditory learners tend to learn better when the subject matter is reinforced by sound. These students would much rather listen to a lecture than read written notes, and they often use their own voices to reinforce new concepts and ideas. These types of learners prefer reading out loud to themselves. They aren’t afraid to speak up in class and are great at verbally explaining things. Additionally, they may be slower at reading and may often repeat things a teacher tells them.

How to cater to auditory learners: Since these students generally find it hard to stay quiet for long periods of time, get your auditory learners involved in the lecture by asking them to repeat new concepts back to you. Ask questions and let them answer. Invoke group discussions so your auditory and verbal processors can properly take in and understand the information they’re being presented with. Watching videos and using music or audiotapes are also helpful ways of learning for this group.

3. Kinesthetic learners

How to recognize kinesthetic learners in your class: Kinesthetic learners, sometimes called tactile learners, learn through experiencing or doing things. They like to get involved by acting out events or using their hands to touch and handle in order to understand concepts. These types of learners might struggle to sit still and often excel at sports or like to dance. They may need to take more frequent breaks when studying.

How to cater to kinesthetic learners: The best way teachers can help these students learn is by getting them moving. Instruct students to act out a certain scene from a book or a lesson you’re teaching. Also try encouraging these students by incorporating movement into lessons: pacing to help memorize, learning games that involve moving around the classroom or having students write on the whiteboard as part of an activity.

Once kinesthetic learners can physically sense what they’re studying, abstract ideas and difficult concepts become easier to understand.

4. Reading/writing learners

How to recognize reading/writing learners in your class: According to the VARK Modalities theory developed by Fleming and Mills in 1992, reading/writing learners prefer to learn through written words. While there is some overlap with visual learning, these types of learners are drawn to expression through writing, reading articles or books, writing in diaries, looking up words in the dictionary and searching the internet for just about everything.

How to cater to reading/writing learners: Of the four learning styles, this is probably the easiest to cater to since much of the traditional educational system tends to center on writing essays, doing research and reading books. Be mindful about allowing plenty of time for these students to absorb information through the written word, and give them opportunities to get their ideas out on paper as well.

Embrace all types of learning

Understanding these different learning styles doesn’t end in the classroom. By equipping students with tools in their early years, teachers are empowering them for their futures. Pinpointing how a child learns best can dramatically affect their ability to connect with the topics you’re teaching, as well as how they participate with the rest of the class.

Now that you have some tactics in your back pocket to accommodate different ways of learning, you may be curious about classroom management strategies. Learn more in our article, “Proven Classroom Management Tips for Preschool Teachers.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was originally published in 2018. It has since been updated to include information relevant to 2020.