Feb 6, 2022 This blog explores when typical children combine words, and provides some activities to do at home to help your child perform this skill.

One of the most worried about concerns for parents regarding child development is to know when their child will be able to communicate effectively. It’s so much easier when they can tell you what they want, need, or if anything is wrong. Please remember, especially in their early years, kids develop at different times depending on their hereditary and environmental situations.

If there is a syndrome, disorder, or cognitive impairment, it will affect your child’s ability to learn and utilize language.

Language Development with Speech Blubs

Speech Blubs is a fantastic speech therapy app with a library of more than 1,500 activities, face filters, voice-activated activities, and educational bonus videos. Explore everything from “Early Sounds” to the “Build a Sentence” section and watch your child learn right away!

Boost Your Child’s Speech Development!

Improve language & communication skills with fun learning!

Language Development Process

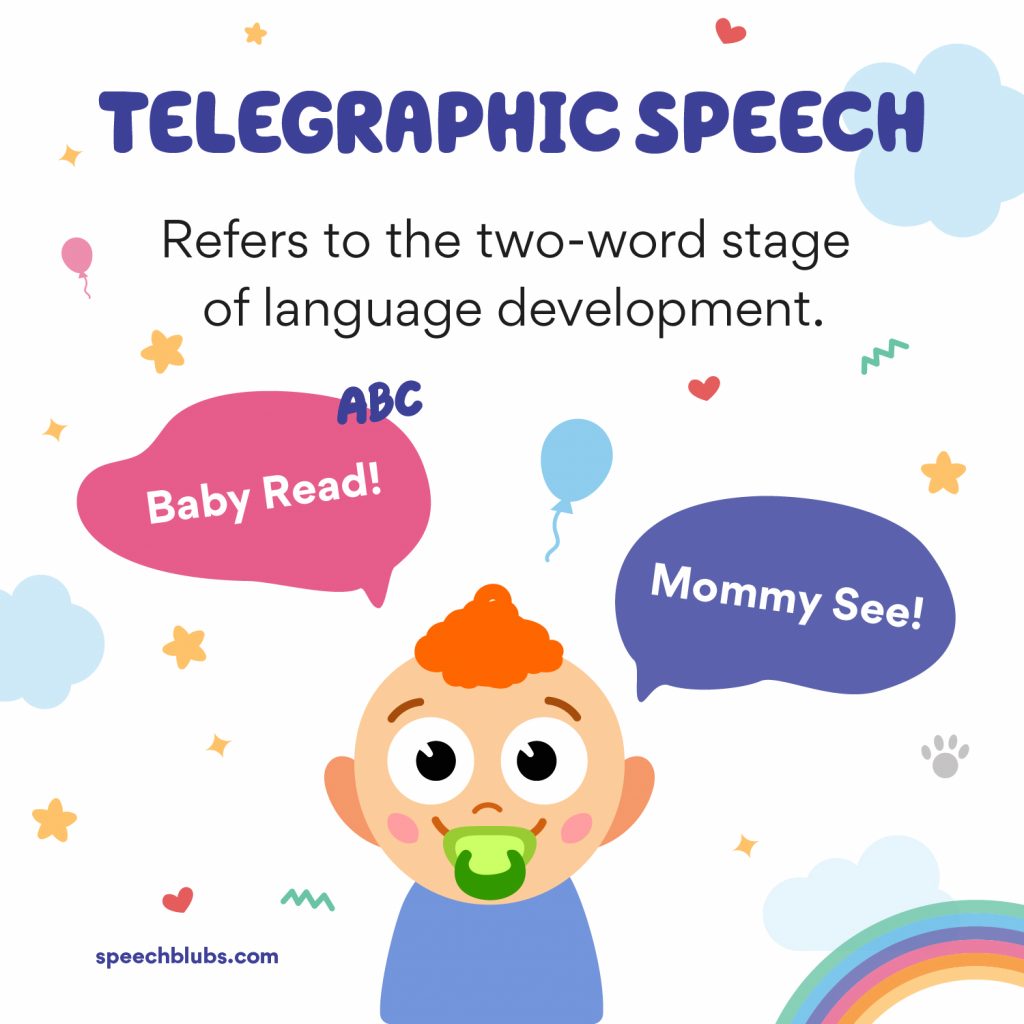

Telegraphic speech refers to the two-word stage of early childhood language development. For example, your baby will say “Mommy See!” or “Baby Read!”

As far as developmental milestones go, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), a child should say his first word by 15 months of age. Another milestone that gets less attention, but is also important, is when children start to string word combinations together.

When a child first starts to attempt this milestone, their combinations will be nouns and actions, such as “mommy go,” or “daddy up.” As their language skills develop and improve, they will start to include things like verbs (actions).

An example of this might be, “car go.” These combinations that include verbs are important as they set the stage for the child’s grammar skills to develop. Children should be combining two words together by 24 months of age (Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents (3rd ed.)).

A recent study looked at children’s first words and first word combinations, and whether delays in either of these milestones predicted later language problems. Interestingly, children who were late combining words were more at risk for future problems with language than children who were late with their first words (Journal of Early Intervention, 38 (1) (41–58)). This means that if your child is delayed in speaking, it’s not as important as when your child starts combining words.

As a speech pathologist, I get a lot of questions from parents as their child develops through these stages and enters toddlerhood. Here are some frequently asked questions answered about child development!

Are “thank you” and “night-night” examples of word combinations?

Many children use these words early on and parents think that they are using two-word combinations. However, these phrases are “chunked” and are memorized. This is different than learning two different words and combining them together. If your child is saying, “thank you, mom,” then that’s an example of combining two different words.

My child uses a ton of single words. Is he ready to combine them?

This comes from SLP Lauren Lowry in her article “Combining Words Together: A Big Step in Language Development” where she says that before a child can combine two words together, he must be able to:

1. Use a variety of words

Children need more than just nouns (names of people, places, and things) in their vocabulary to combine words. Once they can use some early verbs (action words like “go,” “pour,” or “give”), adjectives (words that describe like “hot,” “big,” or “fast”), and/or prepositions (location words like “on,” “in,” or “off”), they have the building blocks to combine words together. These words are typically developed by 18 months of age.

2. Express two ideas

Before expressing two ideas with two-word combinations, children can usually express two ideas by using a word and a “supplementary” gesture, which adds additional information to the word that is spoken. For example, when a child points to the cookie jar and says “Mommy,” his message has two ideas: he wants Mommy to give him a cookie.

Or when a child does an action for “big” with his arms while pointing to a large teddy bear, his message has two ideas: the bear is big. This shouldn’t be confused with the child’s use of gestures that match the meaning of his word (e.g. pointing to a cookie and saying “cookie”), as this only expresses one idea.

When a parent tells me that their child is using more than just nouns, then their child is probably ready to start combining words into phrases.

My child isn’t combining words, should I be concerned?

If your child is 24 months or older and not combining words, it’s important to talk to your pediatrician and get a referral for a speech-language pathologist. They will assess your child’s skills and development to determine if speech therapy is warranted.

5 Ways to Help Your Child Combine Words

1. Follow your child’s lead

Children need practice and repetition when it comes to sending and receiving verbal messages. In order to encourage voluntary communication, you need to follow your child’s lead and see what he/she is doing.

Wait for him/her to send you a message and give them a chance to respond before jumping right in. Make sure you get down on his/her level and comment on everything he/she is doing.

2. Emphasize a variety of words

When you play and interact with your child, emphasize new words that are based on his interests at that moment. Use actions and your voice to make these new words stand out.

Think about highlighting words other than just nouns, such as simple verbs (e.g. “stop,” “push,” or “wash”), adjectives (e.g. “small,” “soft,” or “cold”), and prepositions (e.g. “in,” “on,” “down,” or “up”).

Verbs are especially important for building early sentences and for the development of children’s grammar skills. Play with a teddy bear to model the words!

3. Model short, grammatical sentences

Even though children’s first-word combinations lack proper grammar (e.g. “go car,” “want juice,” or “me up”), it’s important that you provide your child with models that are grammatically correct. This means you shouldn’t imitate his poor grammar and vocabulary.

Make sure you are talking to them in short, simple phrases, but using correct grammar. This helps your child understand how words are used together and what the words mean. For example, if your child says “go car” when he is getting in the car, you can say “You are going in the car.”

4. Expand your child’s words

You can expand your child’s language by using his single word in a short sentence. If your child says “fast” while pushing a car, you can turn that into a little sentence like “The car is fast!” Or, if he smiles while eating a cookie and says “cookie,” you can say “It’s a yummy cookie.”

5. Add gestures to your words

When you use gestures while you speak, it shows your child how to use gestures and words at the same time. This will prepare your child for using supplementary gestures.

Get started with Speech Blubs

Cancel anytime, hassle-free!

The two-word stage is the third major period in the language acquisition of children, following the one-word stage.

Two-Word Stage Age

The two-word stage typically occurs at the age of 18 to 24 months and consists of toddlers using two-word phrases in their speech.

At this stage, toddlers continue to develop their vocabulary and the range of sounds that they can produce. They are able to use two-word phrases that are dense in content words (words that hold and convey meaning); however, function words (words that hold sentences together) are beyond the ability of toddlers at this age so are rarely used.

The sentences produced at this stage consist primarily of nouns and verbs and, despite the lack of function words, toddlers tend to use the correct grammatical sequence in their sentences. Toddlers will enter this period with around 50 words in their vocabulary, but by 24 months they may know over 600 words! ¹

The Two-Word Stage in Child Language Acquisition

It is undeniable that toddlers at the two-word stage can produce meaningful utterances that make sense grammatically, however, their speech is still clearly unlike adult speakers. They still have a limited vocabulary as they haven’t developed the ability to use function words such as articles, auxiliary verbs and subject pronouns.

A toddler’s development of syntax can be observed at this stage from the increasingly complex words that they put together to communicate with adults. They begin to learn how to express semantic relations with actions, objects, entities, and locations, and also start forming commands and questions.

Two-word stage examples

| Word type | Two-word phrase | Possible meaning | Semantic relation expressed |

| Verb + noun | «Read book.» | Can you read the book? | Action + Object |

| Pronoun + verb | «He run.» | He is running. | Agent + Action |

| Pronoun + noun | «My cookie.» | That’s my cookie. | Possessor + Object |

| Noun + adjective | «Mummy busy.» | Mummy is busy. | Agent + Action |

| Noun + verb | «Daddy sleep.» | Daddy is sleeping. | Agent + Action |

| Noun + Noun | «Toy floor.» | The toy is on the floor. | Entity + Location |

| Noun + adjective | «Car shiny.» | The car is shiny. | Entity + attributes |

A major component of language development comes from toddlers repeating words or phrases that they hear adults use. In this process, they will negate the function words that adults use and only use the keywords.

Adult: «Look, the dog just jumped!»

Toddler: «Dog jump!»

Example of Pivot Words in the Two-Word Stage

Children follow simple rules to generate their two-word utterances. They tend to build phrases around a single stable word rather than choosing two terms of the same status.

Their phrases are built around ‘pivot’ words and open words. Pivot words are high-frequency words that are typically determiners or prepositions and are always in a fixed position (either the first or second word). They can be used in conjunction with a wide variety of words, making them a useful part of a child’s vocabulary. ²

Open words make up the content of the two-word phrase and are often a noun or a verb. These words can be interchanged as the first or second word of a phrase and may also be used in isolation.

First-word pivot — All gone.

The example word ‘all gone’ represents a pivot that’s used as a first word. A toddler may use the word in a variety of situations: ‘all gone sweets’, ‘all gone bread’ or ‘all gone toy’. It is unlikely for the toddler to use the pivot word as the second word of a phrase, which is composed of an open word.

Second-word pivot — Off.

Second-word pivots are used less frequently than first-word pivots. The word ‘off’ can be used in a variety of ways: ‘TV off’, ‘light off’ or ‘shoe off ‘. Similarly to first-word pivots, a child is unlikely to use a second-word pivot as the first word in a phrase.

Interpreting the Meaning of Two-Word Phrases

A toddler at this stage will find it difficult to express their thoughts clearly to adults since their vocabulary limits them. Toddlers can assign meaning to words in several ways, which is difficult to interpret with confidence because of the lack of syntactic markings in the language. ³

A word referring to a whole object.

A word that a child uses will refer to the entire object, not to any of the constituent parts.

A child may learn the word ‘flower’, and then use it to name any plant that it sees.

It could be that the toddler isn’t able to perceive the difference between the plants and flowers, or the toddler may settle for using the word flower because there aren’t any alternatives in their vocabulary.

Considering the context

It can be difficult to figure out what a toddler is trying to say without considering the broader context. Adults must pay close attention to the child’s body language when they are trying to speak as they may provide clues by looking or pointing to a relevant object.

The context is equally important for the toddler that is trying to understand what the adult is saying.

Common Mistakes in the Two-Word Stage

Toddlers haven’t yet achieved full command over the pronunciation of words and they will display common errors in their speech.

Assimilation

The pronunciation of a word is affected by a particular sound in the word. A toddler will replace a difficult sound with a sound that is more familiar with.

Toddlers often struggle with bilabials, which are consonant sounds made by pressing the lips together, such as p, b, and m sounds. They find it much easier to produce the same sounds in a word so they tend to assimilate when they come across difficult words to pronounce. If there’s a bilabial sound in a word, a toddler may use the same bilabial in another part of the word since it’s easier to pronounce.

The word ‘rubber’ may be articulated as ‘bubber’.

Gliding

Gliding is when liquid sounds (l and r) are replaced with glide sounds (w and y). It’s a normal part of a child’s language development process and usually disappears at 5 years old.

The word ‘red’ may be articulated as ‘wed ‘.

Cluster reduction

A child may have difficulty pronouncing a cluster of consonants in a word and reduce it by one or more consonants.

The word ‘spoon‘ may be articulated as ‘poon‘.

Weak syllable deletion

This is when an unstressed syllable in a word is not articulated.

The word ‘banana‘ may be articulated as ‘nana’.

Stops

Consonant sounds that have a long airflow are replaced by sounds that have a stopped airflow.

The word ‘sun’ may be articulated as ‘tun’.

Two-Word Stage — Key Takeaways

-

The two-word stage is the third stage of language development.

-

Toddlers develop the ability to form two-word phrases.

-

The two-word stage usually takes place from 18 to 24 months of age.

-

Toddlers start to develop grammar and syntax.

-

Pivot and open words are used to form phrases to communicate ideas.

-

Toddlers still produce pronunciation errors in their speech.

- Oller. D., et al., Infant babbling and speech, Journal of Child Language. 1976

- JG de Villiers, PA de Villiers, Language Acquisition, Vol. 16. 1980.

- Lightfoot et al., The Development of Children. 2008.

© 2023 Prezi Inc.

Terms & Privacy Policy

There are four main stages of normal language acquisition: The babbling stage, the Holophrastic or one-word stage, the two-word stage and the Telegraphic stage. These stages can be broken down even more into these smaller stages: pre-production, early production, speech emergent, beginning fluency intermediate fluency and advanced fluency. On this page I will be providing a summary of the four major stage of language acquisition.

Babbling

Within a few weeks of being born the baby begins to recognize it’s mothers’ voice. There are two sub-stages within this period. The first occurs between birth – 8 months. Most of this stage involves the baby relating to its surroundings and only during 5/6 – 8 month period does the baby begin using it’s vocals. As has been previously discussed babies learn by imitation and the babbling stage is just that. During these months the baby hears sounds around them and tries to reproduce them, albeit with limited success. The babies attempts at creating and experimenting with sounds is what we call babbling. When the baby has been babbling for a few months it begins to relate the words or sounds it is making to objects or things. This is the second sub-stage. From 8 months to 12 months the baby gains more and more control over not only it’s vocal communication but physical communication as well, for example body language and gesturing. Eventually when the baby uses both verbal and non-verbal means to communicate, only then does it move on to the next stage of language acquisition.

Holophrastic / One-word stage

The second stage of language acquisition is the holophrastic or one word stage. This stage is characterized by one word sentences. In this stage nouns make up around 50% of the infants vocabulary while verbs and modifiers make up around 30% and questions and negatives make up the rest. This one-word stage contains single word utterances such as “play” for “I want to play now”. Infants use these sentence primarily to obtain things they want or need, but sometimes they aren’t that obvious. For example a baby may cry or say “mama” when it purely wants attention. The infant is ready to advance to the next stage when it can speak in successive one word sentences.

Two-Word Stage

The two word stage (as you may have guessed) is made of up primarily two word sentences. These sentences contain 1 word for the predicate and 1 word for the subject. For example “Doggie walk” for the sentence “The dog is being walked.” During this stage we see the appearance of single modifiers e.g. “That dog”, two word questions e.g. “Mummy eat?” and the addition of the suffix –ing onto words to describe something that is currently happening e.g. “Baby Sleeping.”

Telegraphic Stage

The final stage of language acquisition is the telegraphic stage. This stage is named as it is because it is similar to what is seen in a telegram; containing just enough information for the sentence to make sense. This stage contains many three and four word sentences. Sometime during this stage the child begins to see the links between words and objects and therefore overgeneralization comes in. Some examples of sentences in the telegraphic stage are “Mummy eat carrot”, “What her name?” and “He is playing ball.” During this stage a child’s vocabulary expands from 50 words to up to 13,000 words. At the end of this stage the child starts to incorporate plurals, joining words and attempts to get a grip on tenses.

As a child’s grasp on language grows it may seem to us as though they just learn each part in a random order, but this is not the case. There is a definite order of speech sounds. Children first start speaking vowels, starting with the rounded mouthed sounds like “oo” and “aa”. After the vowels come the consonants, p, b, m, t, d, n, k and g. The consonants are first because they are easier to pronounce then some of the others, for example ‘s’ and ‘z’ require specific tongue place which children cannot do at that age.

As all human beings do, children will improvise something they cannot yet do. For example when children come across a sound they cannot produce they replace it with a sound they can e.g. ‘Thoap” for “Soap” and “Wun” for “Run.” These are just a few example of resourceful children are, even if in our eyes it is just cute.

Photo by: Dusaleev V.

Definition

Language development is the process by which children come to understand

and communicate language during early childhood.

Description

From birth up to the age of five, children develop language at a very

rapid pace. The stages of language development are universal among humans.

However, the age and the pace at which a child reaches each milestone of

language development vary greatly among children. Thus, language

development in an individual child must be compared with norms rather than

with other individual children. In general girls develop language at a

faster rate than boys. More than any other aspect of development, language

development reflects the growth and maturation of the brain. After the age

of five it becomes much more difficult for most children to learn

language.

Receptive language development (the ability to comprehend language)

usually develops faster than expressive language (the ability to

communicate). Two different styles of language development are recognized.

In referential language development, children first speak single words and

then join words together, first into two-word sentences and then into

three-word sentences. In expressive language development, children first

speak in long unintelligible babbles that mimic the cadence and rhythm of

adult speech. Most children use a combination these styles.

Infancy

Language development begins before birth. Towards the end of pregnancy, a

fetus begins to hear sounds and speech coming from outside the

mother’s body. Infants are acutely attuned to the human voice and

prefer it to other sounds. In particular they prefer the higher pitch

characteristic of female voices. They also are very attentive to the human

face, especially when the face is talking. Although crying is a

child’s primary means of communication at birth, language

immediately begins to develop via repetition and imitation.

Between birth and three months of age, most infants acquire the following

abilities:

- seem to recognize their mother’s voice

- quiet down or smile when spoken to

- turn toward familiar voices and sounds

- make sounds indicating pleasure

- cry differently to express different needs

- grunt, chuckle, whimper, and gurgle

-

begin to coo (repeating the same sounds frequently) in response to

voices -

make vowel-like sounds such as «ooh» and

«ah»

Between three and six months, most infants can do the following:

- turn their head toward a speaker

- watch a speaker’s mouth movements

- respond to changes in a tone of voice

- make louder sounds including screeches

- vocalize excitement, pleasure, and displeasure

-

cry differently out of

pain

or hunger - laugh, squeal, and sigh

- sputter loudly and blow bubbles

- shape their mouths to change sounds

- vocalize different sounds for different needs

- communicate desires with gestures

- babble for attention

- mimic sounds, inflections, and gestures

-

make many new sounds, including «p,» «b,»

and «m,» that may sound almost speech-like

The sounds and babblings of this stage of language development are

identical in babies throughout the world, even among those who are

profoundly deaf. Thus all babies are born with the capacity to learn any

language. Social interaction determines which language they eventually

learn.

Six to 12 months is a crucial age for receptive language development.

Between six and nine months babies begin to do the following:

- search for sources of sound

- listen intently to speech and other sounds

-

take an active interest in conversation even if it is not directed at

them -

recognize «dada,» «mama,»

«bye-bye» - consistently respond to their names

- respond appropriately to friendly and angry tones

- express their moods by sound and body language

-

play

with sounds - make long, more varied sounds

- babble random combinations of consonants and vowels

- babble in singsong with as many as 12 different sounds

- experiment with pitch, intonation, and volume

- use their tongues to change sounds

- repeat syllables

- imitate intonation and speech sounds

Between nine and 12 months babies may begin to do the following:

- listen when spoken to

-

recognize words for common objects and names of

family

members - respond to simple requests

- understand «no»

- understand gestures

- associate voices and names with people

- know their own names

-

babble both short and long groups of sounds and two-to-three-syllable

repeated sounds (The babble begins to have characteristic sounds of

their native language.) - use sounds other than crying to get attention

- use «mama» and «dada» for any person

- shout and scream

- repeat sounds

- use most consonant and vowel sounds

- practice inflections

- engage in much vocal play

Toddlerhood

During the second year of life language development proceeds at very

different rates in different children. By the age of 12 months, most

children use «mama/dada» appropriately. They add new words

each month and temporarily lose words. Between 12 and 15 months children

begin to do the following:

- recognize names

- understand and follow one-step directions

- laugh appropriately

-

use four to six intelligible words, usually those starting with

«b,» «c,» «d,» and

«g,» although less than 20 percent of their language is

comprehensible to outsiders - use partial words

- gesture and speak «no»

- ask for help with gestures and sounds

At 15 to 18 months of age children usually do the following:

-

understand «up,» «down,»

«hot,» «off» - use 10 to 20 intelligible words, mostly nouns

- use complete words

- put two short words together to form sentences

-

chatter and imitate, use some echolalia (repetitions of words and

phrases) - have 20 to 25 percent of their speech understood by outsiders

At 18 to 24 months of age toddlers come to understand that there are words

for everything and their language development gains momentum. About 50 of

a child’s first words are universal: names of foods, animals,

family members,

toys

, vehicles, and clothing. Usually children first learn general nouns, such

as «flower» instead of «dandelion,» and they

may overgeneralize words, such as calling all toys «balls.»

Some children learn words for social situations, greetings, and

expressions of love more readily than others. At this age children usually

have 20 to 50 intelligible words and can do the following:

- follow two-step directions

- point to parts of the body

- attempt multi-syllable words

- speak three-word sentences

- ask two-word questions

- enjoy challenge words such as «helicopter»

- hum and sing

- express pain verbally

- have 50 to 70 percent of their speech understood by outsiders

After several months of slower development, children often have a

«word spurt» (an explosion of new words). Between the ages

of two and 18 years, it is estimated that children add nine new words per

day. Between two and three years of age children acquire:

- a 400-word vocabulary including names

- a word for most everything

- the use of pronouns

- three to five-word sentences

- the ability to describe what they just saw or experienced

- the use of the past tense and plurals

- names for body parts, colors, toys, people, and objects

- the ability to repeat rhymes, songs, and stories

- the ability to answer «what» questions

Children constantly produce sentences that they have not heard before,

creating rather than imitating. This

creativity

is based on the general principles and rules of language that they have

mastered. By the time a child is three years of age, most of a

child’s speech can be understood. However, like adults, children

vary greatly in how much they choose to talk.

Preschool

Three to four-year-olds usually can do the following:

- understand most of what they hear

- converse

- have 900 to 1,000-word vocabularies, with verbs starting to predominate

- usually talk without repeating syllables or words

- use pronouns correctly

- use three to six-word sentences

- ask questions

- relate experiences and activities

-

tell stories (Occasional

stuttering

and stammering is normal in preschoolers.)

Language skills usually blossom between four and five years of age.

Children of this age can do the following:

- verbalize extensively

- communicate easily with other children and adults

- articulate most English sounds correctly

- know 1,500 to 2,500 words

- use detailed six to eight-word sentences

- can repeat four-syllable words

- use at least four prepositions

- tell stories that stay on topic

- can answer questions about stories

School age

At age five most children can do the following:

- follow three consecutive commands

- talk constantly

- ask innumerable questions

- use descriptive words and compound and complex sentences

- know all the vowels and consonants

- use generally correct grammar

Six-year-olds usually can correct their own grammar and mispronunciations.

Most children double their vocabularies between six and eight years of age

and begin reading at about age seven. A major leap in reading

comprehension occurs at about nine. Ten-year-olds begin to understand

figurative word meanings.

Adolescents generally speak in an adult manner, gaining language maturity

throughout high school.

Common problems

Language delay

is the most common

developmental delay

in children. There are many causes for language delay, both environmental

and physical. About 60 percent of language delays in children under age

three resolve spontaneously. Early intervention often helps other children

to catch up to their age group.

Common circumstances that can result in language delay include:

- concentration on developing skills other than language

-

siblings who are very close in age or older siblings who interpret for

the younger child - inadequate language stimulation and one-on-one attention

-

bilingualism, in which a child’s combined comprehension of two

languages usually is equivalent to other children’s comprehension

of one language - psychosocial deprivation

Language delay can result from a variety of physical disorders, including

the following:

- mental retardation

-

maturation delay (the slower-than-usual development of the speech

centers of the brain), a common cause of late talking - a hearing impairment

- a learning disability

- cerebral palsy

-

autism (a developmental disorder in which, among other things, children

do not use language or use it abnormally) -

congenital blindness, even in the absence of other neurological

impairment -

Klinefelter syndrome, a disorder in which males are born with an extra X

chromosome

Brain damage or disorders of the central nervous system can cause the

following:

-

receptive aphasia or receptive language disorder, a deficit in spoken

language comprehension or in the ability to respond to spoken language -

expressive aphasia, an inability to speak or write despite normal

language comprehension -

childhood apraxia of speech, in which a sound is substituted for the

desired syllable or word

Parental concerns

Language development is enriched by verbal interactions with other

children and adults. Parents and care-givers can have a significant impact

on early language development. Studies have shown that children of

talkative parents have twice the vocabulary as those of quiet parents. A

study from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

(NICHD) found that children in high-quality childcare environments have

larger vocabularies and more complex language skills than children in

lower-quality situations. In addition language-based interactions appear

to increase a child’s capacity to learn. Recommendations for

encouraging language development in infants include:

-

talking to them as much as possible and giving them opportunities to

respond, perhaps with a smile; short periods of silence help teach the

give-and-take of conversation -

talking to infants in a singsong, high-pitched speech, called

«parentese» or «motherese» (This is a

universal method for enhancing language development.) - using one- or two-syllable words and two to three-word sentences

- using proper words rather than baby words

- speaking slowly, drawing-out vowels, and exaggerating main syllables

- avoiding pronouns and articles

- using animated gestures along with words

- addressing the baby by name

- talking about on-going activities

- asking questions

- singing songs

- commenting on sounds in the environment

-

encouraging the baby to make vowel-like and consonant-vowel sounds such

as «ma,» «da,» and «ba» -

repeating recognizable syllables and repeating words that contain the

syllable

When babies reach six to 12 months-of-age, parents should play word games

with them, label objects with words, and allow the baby to listen and

participate in conversations. Parents of toddlers should do the following:

- talk to the child in simple sentences and ask questions

- expand on the toddler’s single words

- use gestures that reinforce words

- put words to the child’s gestures

- name colors

- count items

-

gently repeat correctly any words that the child has mispronounced,

rather than criticizing the child

Parents of two to three-year-olds should do the following:

- talk about what the child and parent are doing each day

- encourage the child to use new words

- repeat and expand on what the child says

-

ask the child yes-or-no questions and questions that require a simple

choice

(Table by GGS Information Services.)

| Language development | |

|

Age |

Activity |

| Two months | Cries, coos, and grunts. |

| Four months | Begins babbling. Makes most vowel sounds and |

| about half of consonant sounds. | |

| Six months | Vocalizes with intonation. Responds to own |

| name. | |

| Eight months | Combines syllables when babbling, such «Ba-ba.» |

| Eleven months | Says one word (or fragment of a word) with |

| meaning. | |

| Twelve months | Says two or three words with meaning. Practices |

| inflection, such as raising pitch of voice at the | |

| end of a question. | |

| Eighteen months | Has a vocabulary between five and 20 words, |

| mostly nouns. Repeats word or phrase over and | |

| over. May start to join two words together. | |

| Two years | Has a vocabulary of 150–300 words. Uses I, me, |

| and you. Uses at least two prepositions (in, on, | |

| under). Combines words in short sentences. | |

| About two-thirds of what is spoken is | |

| understandable. | |

| Three years | Has a vocabulary of 900–1000 words. Uses more |

| verbs, some past tenses, and some plural nouns. | |

| Easily handles three-word sentences. Can give | |

| own name, sex, and age. About 90% of speech is | |

| understandable. | |

| Four years | Can use at least four prepositions. Can usually |

| repeat words of four syllables. Knows some | |

| colors and numbers. Has most vowels and | |

| diphthongs and consonants p, b, m, w, and n | |

| established. Talks a lot and repeats often. | |

| Five years | Can count to ten. Speech is completely |

| understandable, although articulation might not | |

| be perfect. Should have all vowels and | |

| consonants m, p, b, h, w, k, g, t, d, n, ng, y. Can | |

| repeat sentences as long as nine words. Speech | |

| is mostly grammatically correct. | |

| Six years | Should have all vowels and consonants listed |

| above, has added, f, v, sh, zh, th, l. Should be able | |

| to tell a connected story about a picture. | |

| Seven years | Should have consonants s–z, r, voiceless th, ch, |

| wh, and soft g. Should be able to do simple | |

| reading and print many words. | |

| Eight years | All speech sounds established. Carries on |

| conversation at a more adult level. Can tell | |

| complicated stories of past events. Easily uses | |

| complex and compound sentences. Reads simple | |

| stories with ease and can write simple | |

| compositions. | |

|

SOURCE : Child Development Institute. 2004. http://www.childdevelopmentinfo.com. |

- encourage the child to ask questions

-

read books about familiar things, with pictures, rhymes, repetitive

lines, and few words -

read favorite books repeatedly, allowing the child to join in with

familiar words - encourage the child to pretend to read

- not interrupt children when they are speaking

Parents of four to six-year-olds should:

- not speak until the child is fully attentive

- pause after speaking to give the child a chance to respond

- acknowledge, encourage, and praise speech

- introduce new words

- talk about spatial relationships and opposites

- introduce limericks, songs, and poems

- talk about the television programs that they watch

- encourage the child to give directions

- give their full attention when the child initiates a conversation

Parents of six to 12-year-olds should talk to the children, not at them,

encourage conversation by asking questions that require more than a

yes-or-no answer, and listen attentively as the child recounts the

day’s activities.

Additional recommendations for parents and care-givers, by the American

Academy of Pediatrics and others, include:

-

talking at eye level with a child and supplementing words with body

language, gestures, and facial expressions to enhance language

comprehension - talking in ways that catch a child’s attention

- using language to comfort a child

- using correct pronunciations

- using expressive language to discuss objects, actions, and emotions

- playing with sounds and words

- labeling objects and actions with words

- providing objects and experiences to talk about

- choosing activities that promote language

-

listening carefully to children and responding in ways that let them

know that they have been understood, as well as encouraging further

communication -

using complete sentences and adding detail to expand on what a child has

said - knowing when to remain silent

- reading to a child by six months of age at the latest

- encouraging children to ask questions and seek new information

- encouraging children to listen to and ask questions of each other

Television viewing does not promote language development.

When to call the doctor

Parents should call the pediatrician immediately if they suspect that

their child may have a language delay or a hearing problem. Warning signs

of language delay in toddlers include:

- avoiding eye contact

- neither understanding nor speaking words by 18 months of age

- difficulty learning nursery rhymes or simple songs

- not recognizing or labeling common objects

- inability to pay attention to a book or movie

-

poor articulation, such that a parent cannot understand the child more

than 50 percent of the time

KEY TERMS

Apraxia

—Impairment of the ability to make purposeful movements, but not

paralysis or loss of sensation.

Expressive aphasia

—A developmental disorder in which a child has lower-than-normal

proficiency in vocabulary, production of complex sentences, and word

recall, although language comprehension is normal.

Expressive language

—Communicating with language.

Expressive language development

—A style of language development in which a child’s babble

mimics the cadence and rhythm of adult speech.

Receptive aphasia

—A developmental disorder in which a child has difficulty

comprehending spoken and written language.

Receptive language

—The comprehension of language.

Referential language development

—A style of language development in which a child first speaks

single words and then joins words together into two- and three-word

sentences.

Resources

BOOKS

Bochner, Sandra, and Jane Jones.

Child Language Development: Learning to Talk.

London: Whurr Publishers, 2003.

Buckley, Belinda.

Children’s Communications Skills: From Birth to Five Years.

New York: Routledge, 2003.

Oates, John, and Andrew Grayson.

Cognitive and Language Development in Children.

Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004.

PERIODICALS

Howard, Melanie. «How Babies Learn to Talk.»

Baby Talk

69, no. 3 (April 2004): 69–72.

Tsao, Feng-Ming, et al. «Speech Perception in Infancy Predicts

Language Development in the Second Year of Life: A Longitudinal

Study.»

Child Development

75, no. 4 (July/August 2004): 1067–84.

Van Hulle, Carol A., et al. «Genetic, Environmental, and Gender

Effects on Individual Differences in Toddler Expressive Language.»

Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research

47, no. 4 (August 2004): 904–12.

ORGANIZATIONS

American Academy of Pediatrics.

141 Northwest Point Blvd., Elk Grove Village, IL 60007. Web site:

http://www.aap.org.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

10801 Rockville Pike, Rockville, MD 20852. Web site:

http://asha.org

.

Child Development Institute.

3528 E. Ridgeway Road, Orange, CA 92867. Web site:

http://www.cdipage.com/index.htm.

WEB SITES

«Activities to Encourage Speech and Language Development.»

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Available online at

http://www.asha.org/public/speech/development/Parent-Stim-Activities.htm (accessed December 29, 2004).

Dougherty, Dorthy P. «Developing Your Baby’s Language

Skills.»

KidsGrowth.

Available online at

http://www.kidsgrowth.com/resources/articledetail.cfm?id=714

(accessed December 29, 2004).

Genishi, Celia. «Young Children’s Oral Language

Development.»

Child Development Institute.

Available online at

http://www.childdevelopmentinfo.com/development/oral_language_development.shtml (accessed December 29, 2004).

«How Does Your Child Hear and Talk?»

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Available online at

http://www.asha.org/public/speech/development/child_hear_talk.htm

(accessed December 29, 2004).

«Language Development in Children.»

Child Development Institute.

Available online at

http://www.childdevelopmentinfo.com/development/language_development.shtml (accessed December 29, 2004).

Lorenz, Joan Monchak. «Common Concerns about Speech Development:

Part I.»

KidsGrowth.

Available online at

<www.kidsgrowth.com/resources/articledetail.cfm?id=965<

(accessed December 29, 2004).

Rafanello, Donna. «Facilitating Language Development.»

Healthy Child Care America

, Summer 2000.Available online at

http://www.healthychildcare.org/pdf/LangDev.pdf (accessed

December 29, 2004).

Margaret Alic, PhD