I sit down regularly for a session of crossword puzzle solving. I never really give much thought to who created the puzzle and how it became so easy for me to get my daily fix. Just the other day, I thought to myself, where do crosswords come from? What is the history and origin of the crossword puzzle? Is a crossword puzzle based on an ancient formula, or did someone just come up with it in their spare time? I must admit before I became addicted to crossword puzzles, I probably wouldn’t have cared.

All I have really cared about in the past is solving the puzzle in front of me, but now it matters to me! If you have ever wondered about the history of crossword puzzles, you are about to find out.

The history and origins of crossword puzzles:

- The very first crossword puzzle was issued in 1913 in the USA.

- The creator, Arthur Wynne, was born and raised in England.

- At first, crossword puzzles were called Word-Cross.

- The name Word-Cross was later changed to Crossword.

- The first crossword puzzles were diamond-shaped.

- Crossword is inspired by a game called Word Squares.

- Newspaper publications started publishing the crossword puzzle shortly after 1913 in both the USA and the UK.

- The world’s very first crossword puzzle book was published in 1924 in the USA.

- The first computer crossword game became available in 1997.

So, there you have it. As it turns out, we have Arthur Wynne to thank for the convenient access we have to crossword puzzles. I have never heard of him before, and if you are a newbie (or even an avid puzzler), you might not have heard of him either. I, for one, am very grateful he created the puzzle game as I find crosswords to be mentally challenging, and they give me a sense of purpose and achievement.

If you are just as uninformed as I was up until now, you might want to learn a bit more about the history and origins. Read on below to find out a bit more on each of the abovementioned pointers.

How Crossword Puzzles Came to Be

The history of crossword puzzles is not particularly complex. In fact, when you read through the history and origins below, you will come to realize that Arthur Wynne created the game for fun and because of his love of a good word puzzle (or brain teaser).

It seems that Arthur Wynne was quite the puzzler in his youth, and because he got a taste for the joy of solving challenging puzzles, he wanted to create one of his own. Perhaps creating crossword puzzles was Arthur Wynne’s ultimate puzzle in the end. Let’s jump right in to learn a bit more:

1. The very first crossword puzzle was issued in 1913 in the USA.

Something you might have wondered is when the very first crossword puzzle was ever created and published.

The very first time anyone ever saw a crossword puzzle was in a newspaper called the New York World, in the United States, of course. It was the Sunday edition on 21st December 1913 that featured it. It was published by a journalist called Arthur Wynne – you already know this. But why, you ask? The editor had asked Wynne to provide the Crossword for the edition as a feature in the entertainment section. And as you know, Arthur obliged.

2. The creator, Arthur Wynne, was born and raised in England.

Some think that the inventor of the crossword puzzle was actually American, but that is not true. Arthur Wynne was born in Liverpool, England, but only invented the crossword puzzle after he had relocated to the USA. While the creator of the crossword puzzle is British, the puzzle itself is actually from American origins.

3. At first, crossword puzzles were called Word-Cross.

Was the Crossword always called a crossword? No, actually, it wasn’t. When the game first appeared in the New York World newspaper, it was called “Word-Cross”. In the early days of crossword puzzles, everyone referred to it as Word-Cross, but that didn’t last too long at all.

4. The name Word-Cross was later changed to Crossword.

It almost seems as if the name “Word-Cross” was not meant to be and soon the name was changed to “crossword”. The change in the name was not on purpose. In fact, it was the result of a typo that involved leaving out the hyphen and switching the words around. The misprint calling the puzzle a “crossword” seemed to stick. And that is the very reason why we call it a crossword puzzle today instead of Word-Cross.

5. The first crossword puzzles were diamond-shaped.

If you always thought that crossword puzzles look like they do now, you are mistaken. In fact, the first crossword puzzles created and published were diamond-shaped. To many, the idea of the crossword puzzle being a diamond shape seems weird, but it’s really not, as it appeared it was a variety of shapes at that time.

The shape of the crossword puzzle appears to be something that Arthur Wynne played around with, as in addition to his initial diamond shape design, he also created vertical and horizontal puzzles. A while later, he added blank black squares to create separations in the puzzle grid.

6. Crossword is inspired by a game called Word Squares.

At this point, I wasn’t quite satisfied with what I had found out about the history of crossword puzzles. I wanted to find out more and you might be wondering a few things too. You might be wondering how on earth Arthur Wynne came up with the crossword puzzle? I certainly did! Did he just think it up one day?

After a bit of research, I found out that this is not quite the case. Arthur Wynne did have some inspiration for his creation. In fact, he based his puzzle game on a game he was exposed to in his youth, called Word Squares.

Word Squares (specifically Sator Square) is a game that was found in ancient Pompeii. This game was not exactly like crossword puzzles. Instead of having to solve clues to fill the squares on the grid, players were provided with a list of words to use. They were required to place the worlds on the grid in such a way that they read the same both up and down. That, of course, is not how a crossword puzzle works. It’s clear that crossword puzzles are not “based” on Word Squares, but rather inspired by it.

7. Newspaper publications started publishing the crossword puzzle shortly after 1913 in both the USA and the UK.

It was through newspaper publications, after the initial release in the New York World that made crossword puzzles as popular as they are today. Without appearing weekly in the New York World newspaper, crossword puzzles may never have been as popular as they are right now. After that first publication, the crossword puzzle started making its way to other publications. According to Alan Connor’s “Crossword Century”, It then appeared in the Pearson’s Magazine in England in 1922. After that, the very first New York Times crossword puzzle was published in 1942.

8. The world’s very first crossword puzzle book was published in 1924 in the USA.

The next thing to wonder about is crossword puzzle books. How did they come about? Who created them, and are they computer-generated crosswords? Initially, it didn’t add up for me. First, there was Arthur Wynne, creating his own crossword puzzles, which were then shared with the New York World readership. And then other publications in the United States and the United Kingdom started publishing them, but how did complete crossword puzzle books come about?

The very first book of crossword puzzles called “The Cross Word Puzzle Book” was published in 1924 in the United States. This book currently features in the Guinness World Records. This first publication was nothing new, so to speak. Instead, it was a collection of all the crossword puzzles that had already appeared in the New York World. The book was such a success that it spurred the publishing company on to be the renowned company it is today. Of course, the publishing company involved still publishes compilations of crosswords today, and these books are extremely popular.

9. The first computer crossword game became available in 1997.

Another question you might have is how crossword puzzles made the jump from newspapers and compilation books to computerized games and mobile apps. You might find it interesting to know that the very first computerized version of crossword puzzles was only made available in 1997 and was created by a software company called Variety Games. The game itself, you might know it, is called “Crossword Weaver”. Nowadays, there are a multitude of crossword puzzle apps that you can play on your phone.

Make Crossword Puzzles a Part of Your Current & Future Life

While crossword puzzles have a history that is uncomplicated and interesting, there’s no reason to get stuck on the past. Instead, look to the future. Solving crossword puzzles can relieve stress, promote cognitive thinking, and provide a worthy way to spend your time. If you don’t already put time aside for solving crossword puzzles, think about making it a part of your life now and in the future.

At the beginning of this year, Wordle exploded. Scores flooded social media, a hundred spinoffs launched every week, and news sites rushed to share daily clues for solvers. But this isn’t the first time a word game has taken the world by storm.

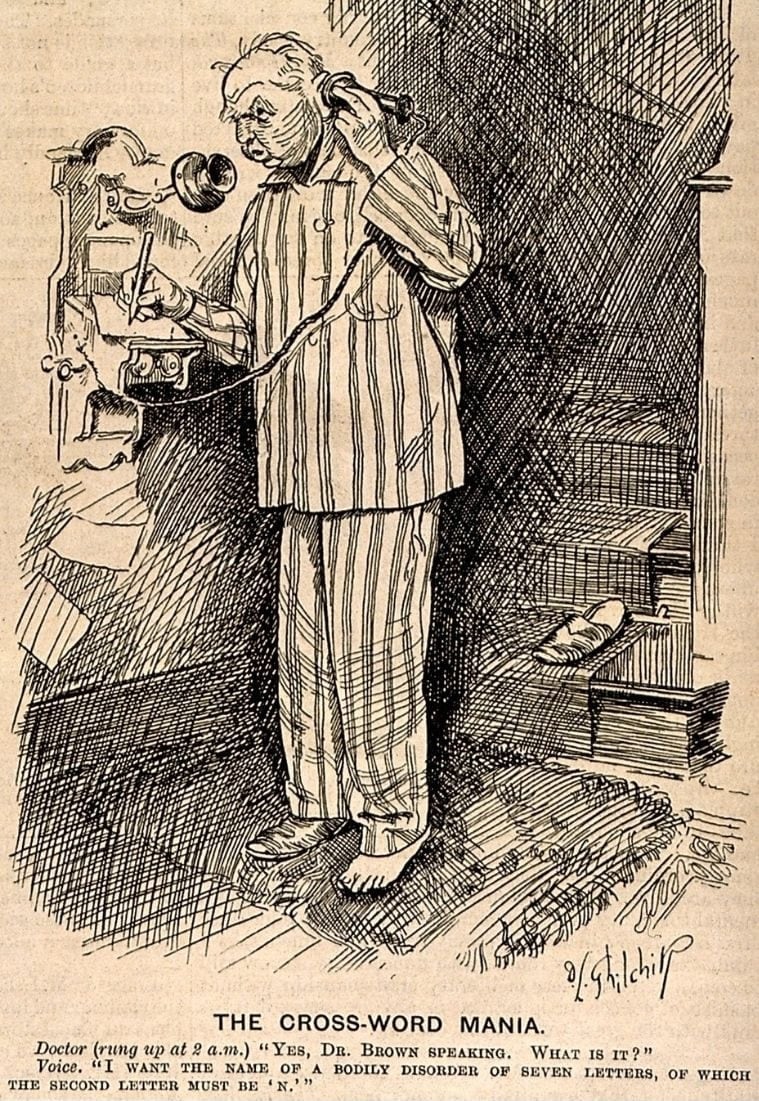

In the early 1900s, a different ‘mania’ gripped the public — crossword mania. Yes, that black-and-white grid that’s seldom finished today, was the central, glamorous hobby for millions in the Anglosphere. This craze manifested in crossword-themed clothing, parties, wedding announcements, aid dictionaries in trains, and even distracted athletes in locker rooms.

But where did it all begin?

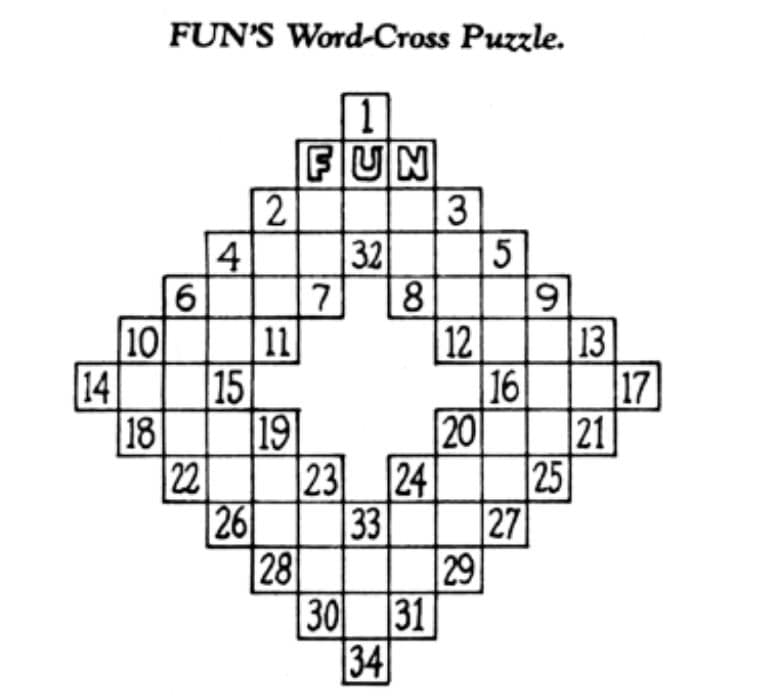

The first published (and thus, known) crossword was made by Arthur Wynne, an editor at American newspaper New York World. Wynne ran a Sunday supplement called FUN, and was looking for something to fill the pages for December 21, 1913. Inspired by word puzzles from his native England (Wynne was a migrant from Liverpool), he created and ran a diamond-shaped puzzle in the paper. Wynne called it a ‘word-cross’, with a list of clues for 32 mystery words:

This ‘word-cross’ was meant to be a one-time game, since it was labour-intensive to create and print in 1913. But FUN’s readers were hooked, and demanded a new ‘word-cross’ every weekend — Americans hadn’t seen it before, so it was a fascinating new hobby. The name was later changed to ‘cross-word’ due to a typesetting mistake, and voila: the modern crossword puzzle was born.

As more papers in the US and UK picked it up, the crossword morphed into the criss-cross grid we know today. Things truly exploded in 1924, when the then-fledgling publishing house Simon & Schuster published the first crossword book, which came with an attached pencil. The book was a massive hit, and cemented Simon & Schuster’s place in the industry.

Today, many might know The New York Times as the holy grail for crosswords. But interestingly, the Times refused to carry crosswords for a long time, once even publishing a column calling it a ‘sinful waste of time’. However, when Pearl Harbour happened, the paper changed its mind. It noted that readers needed a source of comfort in a worrying era, where they spent long hours at home. Sounds familiar?

December 21, the day Wynne published his first puzzle, is now celebrated as National Crossword Day. His original grid is solvable even today, showing how a well-made puzzle stays evergreen. It has a few archaic words in there that might stump you, but give it a try anyway. How often do you get to relive something from 1913?

Link to the answer key for Arthur Wynne’s crossword.

More from Express Puzzles & Games

History Crossword | On India’s Freedom Movement

Movie Crossword | Spotlight on Cinema: An Ode to the Silver Screen

Halloween Crossword | Darna Mana Hai: A Horror Puzzle

Celebrity Crossword | 80 Years of Amitabh Bachchan

For more puzzles, event alerts and bite-sized brainy fun, follow @iepuzzles on Instagram.

Devotees of all kinds of crossword (cruciverbalists, some people coyly call them) will today be saluting the memory of a Liverpool man who emigrated to the United States, abandoned onion farming for journalism, became editor of the New York World, and on 21 December 21, 1913 filled a spare space in his paper with a device that he called a word cross, thus ensuring his name would be honoured today as the inventor of crosswords.

Only curmudgeons would point out at this moment that this claim is a little dubious. Arthur Wynne himself was quick to acknowledge that the idea was as old as the language, and the origins of the puzzle that he created can be plausibly shown to go back at least as far as Pompeii. And though his New York World puzzles continued, it was not until two young men called Simon and Schuster, whose publishing house would go on to give us Ernest Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald, put puzzles into a book 11 years later that they really caught on.

The first newspaper in Britain to use them seems to have been the Sunday Express in 1925. The then Manchester Guardian followed four years later, 13 months ahead of the Times.

But it also has to be said that crosswords today bear about as much resemblance to Wynne’s pioneering number as does the Goldberg Variations to Chopsticks. Wynne’s puzzle was shaped like a diamond. All you had to do was to fill in the answers to questions like «the plural of is» (3) and «what artists learn to do» (4) – even if one or two demanded more erudition («the fibre of the gomuti palm», the answer to which was «doh».)

Today’s familiar black squares were in those days unknown. The art form has evolved in different ways in different countries, but here there are now essentially three varieties: the quick (as in today’s Guardian Review,) the cryptic, below the weather on the penultimate page of this section, and the supercryptic, for ace solvers only, like Azed in tomorrow’s Observer.

The quick is sometimes thought to be simple but that isn’t always the case: a clue may simply say «draw», but that’s a word whose alternative meanings command a whole column in any thesaurus.

It’s the cryptic and supercryptic, though, that are serious business. Over the years, ingenious hands have developed more and more techniques for making their solvers sweat. The Observer was the pacemaker here, unleashing on its customers first Torquemada and, after him, Ximenes, both named after Spanish inquisitors. Ximenes was Derrick Somerset Macnutt, who taught me Greek at Christ’s Hospital school, not a happy experience for either of us. He was one of a school that favoured strict rules for crosswords, which he embodied in a book call Ximenes On the Art of the Crossword, published in 1966.

Some setters still stick to these rules. Others favour the far more libertarian style embodied in the work of John Graham, Araucaria of the Guardian, who died in November. John was an orthodox Anglican minister, but in crossword terms he was a joyous heretic, who, strict Ximeneans might have considered, deserved to be burned at the stake. Most of his Guardian faithful will tell you there never was, and never will be, a setter to match Araucaria. But some of the younger setters, who revere him as the master, take even greater liberties from time to time.

That’s not to say they don’t observe rules. It is still the case, in most instances, that a clue will contain a definition, equivalent to the word or words you need to install, and a cryptic variation to point you towards it. Or often, at first, away from it: since this is a world in which fiendish is a term of approval and the work of its best protagonists is admired for a phenomenon, rare in most trades, that might be called honest deception. In his 2003 book Pretty Girl in Crimson Rose (8), Sandy Balfour describes his girlfriend’s struggles to get him to solve cryptic crosswords. «That,» she says, rejecting a proffered solution, «is what they want you to think it means.» A clue may include the words «Greek character», which will usually indicate the presence of such letters as mu, nu or pi. Yet the letters you need in this case may make up the name Plato.

Some of the tricks of the trade are now ancient. The use, for instance, of anagrams, whose presence is often indicated by words such as mangled, messy or mutilated. Hugh Stephenson, the Guardian’s crossword editor, has three pages listing such devices in his book Secrets of the Setters. Some enthusiasts disparage the anagram, yet it helps the solver to get the game under way, and at its best can be an enrichment of life – as when carthorse yields orchestra, or Manchester City becomes synthetic cream (they were playing that way at the time), or Britney Spears, Presbyterians. There are also standard cliches which solvers soon spot – a soldier may give you RE, or perhaps GI; an L may give you a learner (as in L plates for learner drivers), although it might also mean left, large, lake or Latin. Hugh Stephenson lists these, too.

One quickly learns to distrust a word like flower, which may mean a daisy or daffodil, but may mean a river (rivers flow: geddit?)

Yet what makes a good setter is above all, ingenuity and invention; so brand new tricks are entering the language of crosswords all the time. And it’s when a setter comes up with a clue that baffles you for 45 minutes and makes you gasp when you solve it that the pleasure of crosswords reaches its peak. There were several in the Guardian prize crossword a week ago, concocted by Paul, a devout Araucarian. For instance, the unXimenean «Tommy Cooper» (1, 4, 2, 7, 4) the answer to which I can say, since the competition is closed, is «a name to conjure with». Our hero today, Arthur Wynne (born Everton 1871, died Clearwater, Florida 1945) would surely have marvelled at that.

Ten favourite clues

1 Amundsen’s forwarding address (4)

2 Bar of soap? (6,6)

3 HIJKLMNO? (5)

4 Ie what oil sheik said cheekily unto girl in gin palace (4,2,1,4,4, 4,3,5,2,1,5,4,4,2)

5 I say nothing (3)

6 (7)

7 O (8,6)

8 O hark the herald angels sing the boy’s descent which lifted up the world (5,9,7, 5,6,2,5,3,6,2,3,6)

9 Poetic scene with chaste Lord Archer vegetating (3, 3, 8, 12)

10Silent film star’s scene at Little Bighorn, as delivered by Spooner (6, 6)

Answers:

1 MUSH. (What Amundsen the polar explorer said to his dogs) – Bunthorne

2 ROVER’S RETURN (the pub in Coronation Street) – source not found; picked out by Colin Dexter, creator of the crossword-loving Morse – source not found

3 WATER (H to O = H20) – source not found

4 WHAT IS A NICE GIRL LIKE YOU DOING IN A PLACE LIKE THIS, EH? (anagram) – Bunthorne

5 EGO (I=Ego; say= eg; nothing= 0) — Enigmatist

6 MISSING. (Ie, the clue is missing) – source not found. This has also been used to give the answer «clueless».

7 CIRCULAR LETTER. Source not found

8 WHILE SHEPHERDS WATCHED THEIR FLOCKS BY NIGHT ALL SEATED ON THE GROUND (anagram) – Araucaria

9 THE OLD VICARAGE, GRANTCHESTER. Occurs in poem by Rupert Brooke: «chaste Lord Archer vegetating» is an anagram for it. The then recently disgraced Lord Archer lived there. – Araucaria

10 BUSTER KEATON: which Dr Spooner, who allegedly mixed up opening consonants, might have registered as «Custer beaten.» – Paul

Araucaria, Bunthorne, Enigmatist and Paul are Guardian setters.

Apr 13, 2023

Photo by: Digital Light Source/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Countless people have enjoyed their Sunday morning cup of coffee while doing the newspaper crossword. It’s a tradition that’s now been around for over a hundred years, dating back to the very first crossword published in a newspaper on December 21, 1913.

New fun on Sunday

Back in the early 20th century, there was no Internet to get your fill of the latest news. Printed newspapers were the main source for the public to find out what was going on in the world.

On December 21, 1913, the New York World newspaper published something no one had ever seen before: journalist Arthur Wynne’s “Word-Cross” puzzle. It appeared in the Sunday edition of the New York World.

Mistake catches on

The “Word-Cross” puzzle was a diamond-shaped puzzle of empty boxes with 31 clues for the words to be filled in. As the puzzle gained popularity, it was mistakenly called a “Cross-Word” and has been known by its misnamed moniker ever since.

Soon, other newspapers were publishing their own versions of the crossword puzzles. By the 1920s, America had fallen in love with the crossword. In 1924 the first book of crossword puzzles was released. It even came with its own pencil so readers could start solving right away!

Challenging puzzles to this day

Ironically, the famed New York Times crossword puzzle didn’t exist back in the day. The editors at the paper believed the puzzles were nothing more than a “primitive form of mental exercise”. The Times, however, did eventually catch onto the craze and millions now look forward to its famous Sunday crossword puzzle.

The popularity of crossword puzzles led newspapers to publish other brain teasers, from word-search puzzles to Sodoku, a fill-in-the-numbers game that was a Japanese sensation before making it big in America. Along with crossword puzzles, readers have plenty of ways to exercise their brains whenever they open up the newspaper.

The first-ever crossword puzzle ran in the New York World newspaper on December 21, 1913.

One hundred years later, the puzzles are still extremely popular and run in newspapers across the country. The crosswords we see today are a bit different from the original «word-cross,» which was in the shape of a diamond and didn’t note «across» or down» moves.

See if you can solve the world’s first crossword puzzle, embedded below:

Wikimedia Commons

Parade magazine has an answer key for the puzzle.

And if the above crossword is too puzzling, NPR has an updated version with some of the more obscure words removed.

Although New York World editor Arthur Wynne is credited as the inventor of the crossword puzzle, The Guardian points out that similar word games can be traced back as far as Pompeii.